A profile of a journalist who, in the name of transparency, does more harm than good in the country. Yes, even transparency can be abused.

“You are the most erudite judges in Slovakia, so I dare to ask: why should we turn off the cameras? When a case is public, it is public,” asked journalist Martin Daňo at a meeting of the Judicial Council, the highest body of judicial self-government, in February almost three years ago. Jana Bajánková, the former head of the Judicial Council, had asked journalists to switch off their video equipment after shooting illustrative shots.

In slight disgrace and apparent reluctance to talk to Daňo, after consulting with a colleague, Bajánková called for a vote: “Who is in favour of turning off video recording technology by the general public?” Eleven judges raised their hands (from Bajánková to the president of Košice regional court Imrich Volkai to the head of the State and Law Institute of the Academy of Sciences Jozef Vozár), four abstained, and no one was against.

Daňo raised a complaint to the Constitutional Court, which judged in his favour two years later. According to the court, the Council had violated Daňo’s constitutional right to information and “the right to freely search, receive and disseminate information”. It means anyone can film meetings of the Judicial Council provided that it does not disrupt the course of the session.

“I am defending the rights of journalists and the public here,” commented Daňo on the Judicial Council vote. That was undoubtedly true in this case. Today, however, despite several such victories, Daňo is a symbol of how transparency gained by law can be abused, and how the hopes for the so-called civic journalism (amateur journalism outside professional editorial boards) could shift into a nightmare.

The Daňo phenomenon

Traditional media sources have been going through difficult times in recent years. The Internet space has deprived them of revenues and has added competition (often by low-quality and conspiratorial content). Many media have been taken over by oligarchs.

Even though it is nonetheless them who bring profound revelations of corruption and fraud, the public is beginning to trust them less and less. According to Eurobarometer, trust in the Slovak press, radio and TV channels has fallen by one fifth since 2011. According to the last year’s representative survey, Slovaks value journalists roughly at the level of shopkeepers.

Martin Daňo, until recently mostly known as an entrepreneur doing business in computers, software, advertising, or an online database of the deceased, entered the world of journalism at the beginning of the decade. “I never wanted to be a journalist in my life, but when I found out what kind of swindlers write news in this country, I thought, damn it, I’ll come here. And until it’s all cleared up, I’ll stay. Once it’s cleared, I’ll leave, there is no more need for Daňo,” he said regarding the launch of his journalistic career last year.

In most of his videos, he walks with one camera on his ear and another one in his hand, showing in a reality-show style the behaviour of politicians, police officers, officials, but also journalists on press conferences. He repeatedly comes into conflicts when he is denied requested information by some civil servant, banned from filming or when he is not let in the office building at all. However, Daňo himself also contributes to conflicts with his verbal or physical aggression.

In seven years of work, he has produced over one thousand videos, with an average viewership of 25,000 views. Every tenth of his videos, which can be a few minutes or even more than two hours, has had at least 50,000 views.

He has 41,000 subscribers on YouTube, which is only a tenth compared to TV Joj, the strongest Slovak medium on YouTube, but still a little more than Fun radio and three times more compared to the channel of Denník N daily or the channel of Štefan Harabin. On Facebook, Daňo’s media page GINN Press has almost 30,000 followers and fans, which are better numbers than any anti-corruption NGO (Transparency has 15,000 fans online).

In addition, his audience is rising at great speed. The number of his subscribers has doubled over the last year and a half, growing on average by 25 or more a day. In autumn 2018, the average monthly number of views increased 2.4 times compared to autumn 2016.

In two public opinion polls carried out last year, he bounced to third place, being the sixth most famous journalist in Slovakia (the first was Ján Kuciak in both rankings). In 2013, the famous Czech moderator and actor Jan Kraus invited him to speak about his career on his talk show. „I admire him and I have respect for what he does,” Kraus said about him one year later.

Abuse of transparency

At the time of Kraus’s announcement five years ago, Daňo’s merits could be discussed, while, unfortunately, today it is not true at all. Among pillars backing all laws are also informal rules of ethics and common decency. It is something that no piece of legislation can regulate. And yet Daňo is a phenomenon that crushes these informal rules, even in the name of transparency. Moreover, his statements often seem to balance on the edge of the law.

The first case of abusing the state’s transparency was when Daňo, as an entrepreneur, got into a dispute with the tax authority over a sanction imposed on him in 2007. To retaliate, he swamped the authority with more than five thousand information requests that he sent within a short period of time on tiny, barely legible pieces of paper containing questions about property, employees, or decisions taken by the tax authority. The fact is that the Information Act does not lay down what physical form these requests should have, but each state authority is obliged to respond to such requests within 8 (exceptionally 16) days.

Shortly after, the former MP Edita Angyal submitted an amending proposal that would have enabled authorities to arbitrarily choose when to respond to an information request. Fortunately, following the pressure from the opposition and the third sector, the amendment did not pass. The courts, however, began to take the argument of “bullying requests” seriously and gradually a precedent was established, allowing for some space for arbitrariness. All in all, in this case Daňo and the like contributed to the restriction of citizens’ rights.

The Minister of Culture stated Daňo’s journalistic work was one of the reasons for tightening the regulation of journalism. Today, you can become a journalist with practically no education or experience – all you have to do is just fill out a short form at the ministry. It gives you the right to hide your sources and the formal status of the “press”. In addition to registration, you are in principle required to publish corrections and answers from the people you write about. The intention was to allow for the broadest possible freedom of the media, which is an important control tool of democracy.

Loose rules work if the media themselves are sufficiently responsible and ethical. With the era of the Internet (where, in fact, anyone can become journalist), the weakening status of the press and the emergence of conspiratorial alternatives, one can no longer take those values for granted. For example, according to a former journalist, the Ministry of Justice started restricting attendance to their business breakfasts exclusively to those who got directly invited, just to make sure Daňo would not come. This, however, meant excluding other journalists who might have been interested in the work of the ministry.

At the end of the day, Daňo and people like him are responsible for the situation where more press conferences with access by invitation only, more regulation and new forms of accreditation can be expected, which means narrowing down opportunities for journalists and the public to de facto control those in power.

“I will secure your popularity”

Why is Martin Daňo’s journalism problematic? Well, there are quite a few issues.

First of all, Daňo is a journalist on one hand and a political figure on the other. As early as five years ago, he ran for the elections to the European Parliament as a Právo a Spravodlivosť (Law and Justice) candidate (he won over 7,400 preferential votes, more than, for example, František Šebej, Martin Poliačik or Ondrej Dostál). A year later he stood for the mayor of his hometown Humenné. However, just before the elections, he was wrongfully excluded due to an alleged administrative error. And last spring, he announced his candidacy for the president and started to diligently collect signatures from Members of Parliament to have his candidacy officially registered.

This is where a question arises: how can a journalist scrutinise politicians and at the same time stay unbiased if he/she also wants to defeat them in elections or cooperate with them in a coalition? And isn’t it true that a journalist aspiring to a political career is, as a matter of fact, motivated to unfair and pell-mell criticism of other politicians just to show himself/herself in the best light? No standard editorial board, be it in Slovakia or abroad, would tolerate someone combining these two professions.

Actually, when collecting signatures in the Parliament, it is quite common for Daňo, who on many occasions declares himself fighter against the corruption of mainstream journalists, to trade signatures of MPs for turning a blind eye to them in his journalistic work.

When Alena Bašistová (former deputy for Sieť (Network)) ran for the mayor of Košice, two months before the elections Daňo offered to help her with the campaign: “You’ll see, I will secure your popularity in Košice…” Bašistová gave him her signature and Daňo in turn harshly and unfairly criticised the front-running candidate J. Polaček, warmly recommending people to vote for Bašistová.

Shortly before the elections, he said in a live broadcast: “I am in Košice – I am convinced that after today – I do not know if it is some good fortune or a presentiment of mine – I am convinced that Mr. Polaček can say goodbye to the mayor’s chair.”

A week later Polaček won convincingly.

Deals with politicians

When Daňo asked for a signature from the MP for Smer (Direction) Erik Tomáš, who is also a native of Humenné, Daňo told him: “I will take the side of Mrs. Vaľová.” Tomáš has not given him the signature yet, but during the elections, Daňo focused his criticism on Miloš Merička, the main challenger of the former mayor for Smer Jana Vaľová.

In December, Vaľová, holding the position of Humenné municipal council member, lost a court case related to unjustified dismissal of a town school director. Daňo defended Vaľová’s unlawful conduct and in the meantime, he was begging her for signature for his presidency. What is more, Daňo has recently founded trade unions (with a motto: our negotiations will be transparent), claiming to defend the interests of employees against the arbitrariness of managers.

And yet, in the past Daňo used to criticise Vaľová’s government in Humenné for a long time, calling her an old witch. As late as in summer last year he labelled her mayorship as “dark age”.

Daňo also turned to MPs for Sme Rodina (We Are Family), who already have their presidential candidate Milan Krajniak, with a proposal for a deal: “If everyone gives me their signature, Krajniak can be spared all questions [in television discussions]. If they don’t give me their signatures, there will be uncomfortable questions [from Daňo to Krajniak].” When he met Krajniak personally he repeated the offer: “Give me your signature, save my time and spare yourself troubles during the presidential debates.”

He even apple-polished Robert Kaliňák (whom he actually could not stand in the past), saying: “If you give me your signature, I will tear Tódová to shreds.” He was talking about Monika Tódová from Denník N daily, one of the most consistent journalists investigating Kaliňák’s cases.

Daňo had similar comments regarding Béla Bugár: “I still have Bugár to talk to, to see if he gives me his signature for my presidency. Because if he does not, I will have to start talking about stuff like Transpetrol, the intervention by NAKA, he knows very well what I mean…”

Can someone, who blackmails politicians in this way, be regarded as a good journalist? Can someone “clear up” the low-quality journalism by dealing with various cases of politicians depending on benefits that can be gained from it?

In a way, it is quite possible though, that Daňo is not as much interested in holding a high office but in obtaining free publicity in national media for his business and himself – which in fact is also misusing the spirit of the Electoral Law, let alone the mission of journalism as such.

Not to mention the fact that he has already announced his interest in running for this year’s elections to the European Parliament – again in the same fashion: by making a deal with some political representatives. “If you give me your party or put me on your party’s ticket so that I can be in political debates, just call me, e-mail me… I am willing to run for the European elections,” he said last November.

Well, then sue me

Another serious issue with Daňo’s work is mixing his impressions with facts and, overall, insufficient fact-checking. This can be clearly seen on the case related to the murder of Ján Kuciak and his fiancé.

Similarly to the then-Prime Minister Robert Fico, Daňo started claiming with no evidence at all that organisers of the protests Za Slušné Slovensko (For a Decent Slovakia) were paid for their activities, same as journalists who covered the protests. What is more, although Daňo often calls for freedom of speech and freedom of assembly as part of his work, he does not seem to let others enjoy such freedoms: “If I were in Fico’s place… I would put them to jail right away – they should have been put away already when they were organising those protests – lock ’em up in prison, all of them without mercy and investigate them really hard.”

Daňo refused the protest marches right from the beginning, saying they were manipulated, even though they were actually calling for accountability of people from Smer (Direction), a party that he himself regularly used to blame for corruption in the past. He claimed that actors from the Slovak National Theatre who joined the protest marches got paid for their participation (Daňo did not provide any proof).

When the marches turned into mass events, Daňo started putting them down by saying that too few people participated. When the number of protesters reached several tens of thousands of people in the second week of March, he claimed, just out of spice, that they were merely 5 thousand – despite the fact various media consistently counted the participants. Claiming falsehood in spite of clear facts is not journalism, but demagogy and politicking.

In March, Daňo and his fellow Rudolf Vaský made an interview with Marián Kočner where they grumbled together at mainstream journalists. There was not a single critical question to Kočner, who had, in fact, threatened Daňo before the medialised murder. Just on the contrary, during the whole interview Daňo was nodding to the monologue of the businessman who had been involved in many past cases. When Kočner mentioned journalists from TREND weekly, who had been tracking his cases, and called them hens, Daňo laughed along with him amicably.

“I am not his lawyer, morning-noon-evening, Kočner-Kočner-Kočner… are there no other problems? …Every single day there is some new lie about Kočner,” Daňo said last year in summer.

His approach to Kočner was, actually, very similar to his respectful behaviour towards Štefan Harabin, whom he has been addressing for years as the highest authority in the judiciary (ignoring Harabin’s misdemeanours and fight against transparency in justice), vigorously nodding to his views and regularly covering his disciplinary proceedings.

When Kočner got arrested in the so-called bill case, Daňo started questioning evidence gathered against Kočner. He even published a secret recording of a conversation between the prosecutor Ján Šanta and some journalists recorded in the court hallway, where he distorted what Šanta had said. However, the recording itself did not show anything unlawful or non-standard.

Moreover, he suggested several times during the year that Kuciak had not even been an extraordinary journalist and even that his colleagues had misused him and thus indirectly sacrificed him.

“They turned the young boy in a victim, they made him write about the same things… why didn’t Vagovič deal with it? Was he afraid? Or maybe it was their intention to make a victim out of a young good-mannered boy who gets killed later so that they can create an icon of some “decent revolution”. The stuff he [Kuciak] wrote about – no one understood that… they had tasked him with it on purpose so that they could make use of his sacrifice…” Daňo failed to provide evidence of this sophisticated conspiracy.

Towards the end of the year, past all bearings, Daňo published photos of young women that had allegedly been found in Kuciak’s phone – it was claimed that Kuciak had been taking these photos on bus stops like some pervert. The video Daňo created together with Vaský has so far reached 26,000 views.

One of the photos allegedly showed the bottom of the Denník N journalist Monika Tódová, Daňo explained, bursting into laughter together with his colleague. However, you only need a few clicks on the Internet and you can easily find out that the said photo along with all presented photographs were simply downloaded from all kinds of web pages. There were many viewers who reproached him for this in the video comments. Daňo made no reaction, and the video is still online in its original version.

The following day Daňo admitted in a live broadcast that “some of the photographs” were illustrative. But he went on insisting there really were some pictures of bottoms of young women in Kuciak’s file and if someone does not believe him, he/she should sue him. Well, that is really a showpiece of investigative journalism.

By the way, when the daily Plus jeden deň mistakenly reported on a music videoclip supposedly featuring Alena Zsuzsová (the young woman in the video turned out to be someone else), Daňo got outraged and again criticised standard media. “I have never published any piece of information without checking it first… Such people belong to prison… catch them and put them to jail,” Daňo voiced his recommendations.

A greasy hair and a fat pig

Another malady of Daňo’s work that is worth mentioning is his tendency to take things too personally. If you criticise him, you are a fool and get told to clear off from his channel. Or someone has surely paid you for criticising him. And that is, actually, the best way to come off because if you criticise Daňo too much, he invites his fans to dig some dirt on you, saying that “…we might have a close look at the guy”. Or he starts looking into the private life of civil servants (R. Krpelan, D. Guspan) who have not obliged him with something.

Having said that, Daňo has no problem declaring in other occasions: “If you tell me what I am doing wrong, I will be happy to have a think about it.”

There are indeed quite a few paradoxes in Daňo’s work. On one hand, he can give emotional speech to defend handicapped persons or Romas, on the other hand, he repeatedly assaults people because of their appearance, physical characteristics, or sexual orientation. He nicknames the Slovak President Kiska “greasy hair” or “snake”, the president of the political party Spolu (Together) Beblavý is “Brblavý” (translator’s note: an allusion to the person’s speech defect), the lawyer R. Pala and many others get called “pig heads”, the MP Lucia Nicholsonová has a contemptuous nickname “the gipsy woman”, the leader of Progresívne Slovensko (Progressive Slovakia) Ivan Štefunko is “the Algerian” (he grew up in Algeria), the presidential candidate Zuzana Čaputová is “a double-dealing hooker”, the organiser of protest marches Karolína Farská is, according to his words, “small, repulsive and ugly”, the president of Zastavme korupciu (Stop corruption) foundation Zuzana Petková gets called “mildly retarded” etc. He is good at homophobic comments too – some time ago he even demanded that all homosexuals working in the state administration come out of the closet.

From time to time he makes insulting remarks aimed at migrants and uses ethnic slurs when speaking about foreigners from specific countries, such as Krauts, Dinks or Chinks, although Daňo himself has spent several years in Paris and today he lives just a short way from Bratislava – in Austria.

Beating with iron rods

Another issue with Daňo’s work is quite serious – his calls and plans for violence. “We’ll wipe them off. This is not a threat, it’s a warning that it can happen because they censor their content,” he addressed mainstream journalists.

“They gotta be eliminated… the first to get rid of are corrupted journalists Tódová, Vagovič, Bárdy, Malarová, Valček, Petková… we will get even with them in the first place, the second will be NGOs and after that we’ll start making clean politics here,” he said on another occasion (recently Daňo also blamed Transparency from corruption, accusing us from blackmailing municipal authorities – “If they don’t order an audit, they get bad ranking from Transparency,” – of course, he offers no evidence whatsoever. You can find out how our rankings are created here).

His statements from March last year have even caught the attention of the general prosecutor’s office that started dealing with them. He uttered them shortly after the murder of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová: “Fascist swines: Monika Tódová, Marek Vagovič, Šnídl, the gipsy Ďuriš Nicholsonová, Igor Matovič, Richard Sulík, Andrej Kiska. You’ll drop dead! Lucia Ďuriš Nicholsonová – she should have been killed,” Daňo told his viewers.

When commenting on the Trade Union Law last month he said: “This is absolutely unconstitutional what these degenerate morons have adopted, we will catch them all one day. I personally will be slashing here if they don’t repeal this (fiercely rising an imaginary iron rod in his hand).” Addressing the president of the trade unions in Slovakia’s largest factory, he also added: “Smolinský in Volkswagen, the biggest snake in Slovakia, he will be exemplarily hung by his balls if he does not stop what he’s doing.”

Last summer he wished the Slovak President a fatal accident: “Andrej Kiska will have a first-rate transport… There is a state-of-the-art helicopter waiting for him here… maybe it would be even better if that was the last thing he sees in his life,” he wrote on Facebook.

In his comments, Daňo declares that the only thing that can help is a revolution (“elections are good for nothing”) and he repeatedly suggests that he means a violent revolution. “When you make this kind of protests, you need to be bold. Who will take notice of such peaceful protest… why doesn’t anybody demolish and loot houses of those who have allowed this system to exist for 30 years?” he prodded last week (it is interesting to note that he does not pose this question to Harabin who has held high offices for 20 years). “Yellow vests in Slovakia, that’s a naive idea… what you need here is a brick in your hand, an iron rod in your hand and let these do the work… Hey, you in NAKA, I am not inciting anybody.”

Usually, Daňo cowardly – some would say cunningly – chooses tactics of only implying the need for violence, but he often adds somehow that it is not a threat nor incitement, as that would be illegal. Or he says it is just a parody, although when making videos together with Vaský, they usually present equally serious views as in videos they publish individually. The prosecutor’s office have not taken a final decision in the case of Nicholsonová and others yet (actually, why is it taking so long?).

However, Daňo’s fellow Vaský is, in a different case, already accused of the offence of incitement to violence towards a group of citizens for his statement: “We will use those iron rods to end the revolution; first we will make a list of people who will get beaten… then we will catch them and beat them to death.”

Last year, both the Office of the President and the National Council denied Daňo access to press conferences, or more precisely, suspended his accreditation for entry into the respective buildings due to his aggressive behaviour and threats (Daňo’s accreditation was later renewed in November).

YouTube and Facebook have already blocked Daňo several times on grounds of his hateful speech or defamation.

Bella Daňola

Who is funding his journalistic activities? While with standard media you can easily check their ownership, sales and paid taxes in the Business Register and Register of Financial Statements, it is not that easy with Daňo’s organisation GINN. Both GINN and GINN.PRESS are civic organisations that have no obligation to publish their turnovers. Last year, GINN.PRESS raised €12,000 from the scheme of 2% of tax donations. According to the social media monitor Social Blade, Daňo can be earning similar amounts through his advertising revenue on YouTube.

It remains unclear where the largest portion of the financial support for Daňo’s work comes from because he still has not disclosed his donors, despite repeated promises to do so. In October last year, he opened a transparent account where he has raised €1,200 over the past three months.

His fans sometimes donate him technical equipment for broadcasting. Daňo also promotes Bella Tavola, a company selling kitchenware, during his broadcasting sessions and from time to time he drinks tea served in their cups (“This programme is produced today with the support from citizens, with the support from Bella Tavola, Christmas is coming, they have nice presents, porcelain, knives, everything…”). The company is owned by Michal Mandzák, a lawyer who pleaded Daňo’s case before the Constitutional Court related to his dispute with the Judicial Council. In his several companies, Mandzák states Kochanovce to be his home address, which is a small village right next to Humenné. Today Mandzák is known as the lawyer of Marián Kočner in the bill case that is also covered by Daňo’s news reports (has Daňo ever heard of something like conflicts of interest?).

Although Daňo places high transparency demands on others, he fails to be adequately transparent in his own business activities. On Facebook he states two Slovak limited companies Sysoon and Sysoon Europe as his primary firms. None of these companies deposits their financial statements in the collection of documents, although it is a legal obligation of all companies. Thus the public does not see what business results he has and what taxes he pays. There is, however, another registry clearly showing a simple fact – both companies have arrears of taxes and social security contributions, currently €200,000 in total.

The pattern of failing to present financial statements, indebtedness and going into liquidation recurs in other Daňo’s firms as well.

Passing the „Daňo test”

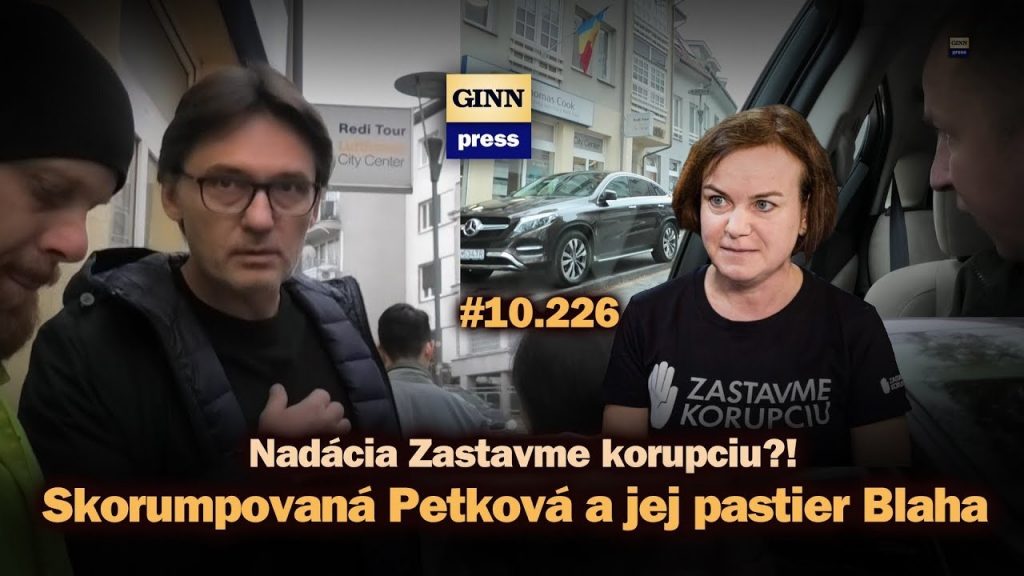

In autumn last year, Daňo caught Michal Blaha, head of the advertising agency Mark BBDO and co-founder of Zastavme korupciu (Stop corruption) foundation, red-handed as he was repeatedly breaching parking regulations and reversing his car in a one-way street. Blaha’s company resides in Zámocká street No. 5, downhill from the Bratislava castle and the Parliament, which is the same address as Mandzák’s law firm.

Blaha explained to Daňo on camera why he is parking across the pavement, saying: “I have an agreement with the police as long as I leave at least 1.5m of space for passage.” When the police came, he paid the fine and moved his car away. Daňo has generalised Blaho’s personal mistake over the whole foundation and its director Mrs. Petková, whom he has started calling corrupted ever since. Even if Blaha did have a corrupt deal with the police – although the mere statement in the video is far from enough to corroborate it – why blackening people who might have nothing to do with Blaha’s parking?

It is true to say, though, that Petková’s reaction to Daňo’s questions regarding Blaha’s behaviour was not quite exemplary either. Instead of simply condemning anybody’s infringements in general, Petková repeatedly hung up the phone, attacked Daňo with questions about sources of his funding and run away from him. Even when personal communication with Daňo must have been unpleasant, her reactions unnecessarily added to Daňo’s legitimacy – after all, this is exactly how politicians with guilty conscience typically escape journalists. In direct argumentation on who is corrupted, Daňo would get the short end of the stick.

Every citizen indeed has a right to get an answer when asking about someone’s own work or about financing of media or the third sector. When Daňo had asked us in the past about Transparency’s former cooperation with Andrej Kiska in a project related to reporting corruption in hospitals, we sent him the answer without delay.

The foundation finally managed to react in a more or less standard way to Daňo’s teasing in the discussion on its Facebook page in December.

Better ignore him?

The question of taking the right approach to Daňo is in general a weak spot of standard journalists as well. They tend to ignore his legitimate revelations such as his victory in the case before the Constitutional Court described above or his pointing out to a loophole in the Act on Conflicts of Interest in connection with the head of the Slovak Radio and Television. But they also rarely cover cases when his work is a miss (although the tide started turning when Daňo pulled out alleged information from Kočner’s file at the end of last year). But how do they want to compete with makers of alternative content and their supporters if they do not write about their work and manipulations?

And yet, it is also a mistake to lower to the level of personal assaults. Again, no matter how revolting Daňo’s attacks may be, it is necessary to keep one’s standard. Marek Vagovič, one of the most appreciated journalists in Slovakia and former boss of Ján Kuciak in Aktuality.sk has recently written on Facebook that “Daňo plays investigative journalist but all he can do is puff in the camera.” There are no doubt more relevant arguments to criticise Daňo than pointing to the functioning of his respiratory system.

By contrast, when trying to win public’s trust, journalists should devote more energy to explaining circumstances of their coverage, whom they addressed, why they actually picked the topic in general etc. This trend of greater openness is starting to flourish especially in the USA, where the alternative scene as well as the President persistently bombard standard media with accusations of misstatements and misinformation. It would also be helpful to use videos more frequently and shoot the backstage of the news reports. It would narrow down the space for conspiracies and video-manipulations.

The toughest question is whether and how journalists such as Daňo could be restricted from access to press conferences. On one hand, journalists from the whole spectrum of views should have access to information and opportunities to ask critical questions. On the other hand, tolerating incitement to violence can really come home to roost someday.

The Office of the National Council’s reasoning as to why they suspended and later renewed Daňo’s accreditation for the Parliament last year seams rather pliable – the law nor the directive define for how long a media accreditation can be suspended and what is in fact meant by disrupting a session. And yet, the main reason stated – threats aimed at MP Nicholsonová – has not been resolved by the prosecutor’s office or the court in any way. Daňo has nevertheless regained the right to enter the Parliament.

A recent example from the USA, when a CNN journalist lost his accreditation for the White House for certain period of time, smacks of a very similar kind of arbitrariness that is currently possible in Slovakia too. When the moods or civil servants change, unclear rules can bring unwanted consequences one day.

There is, however, a lesson to be learnt by all of us who fight for principles of transparency and openness. It is evidently high time to consider more thoroughly the dark side and think of how potential abuse of these principles could be regulated. What if next time there will be a dozen Daňos running around?

Try it in another way

In a sense, Daňo’s work is an ideal example to be used by schools of journalism.

Dealing with a phenomenon like this is also about the ability to realise how distorting it is to draw black-and-white conclusions. Martin Daňo himself has some examples of good work on his account, although, unfortunately, they have become quite rare, especially in the recent years. This will almost always be true about politicians, entrepreneurs or other people whose stories we read in the news.

But Daňo is now above all an example clearly showing how deep a journalist craving for a political career can fall. How destructive for the quality of your work it is when you take things personally and when you report positively on people who agree with you and fawn over you, while staying negative towards those who do not. When you preach something (transparency!), but you practise something else. How untrustworthy it is when you mix facts with assumptions and make up stories based on your personal animosities. When you are unable to accept criticism.

Last but not least, Daňo’s case demonstrates the importance of unwritten rules such as politeness and respect for respondents or colleagues within the work of a journalist. It shows that the need to check possible conflicts of interest and independence is a key challenge for the media.

Although to a much lesser extent, these problems repeatedly pop up in the mainstream media circles too. If only the deterring example of Martin Daňo could drive traditional media to improve their ethics and quality and to draw at least a part of the disillusioned public back from the so-called alternative sources.

Gabriel Šípoš