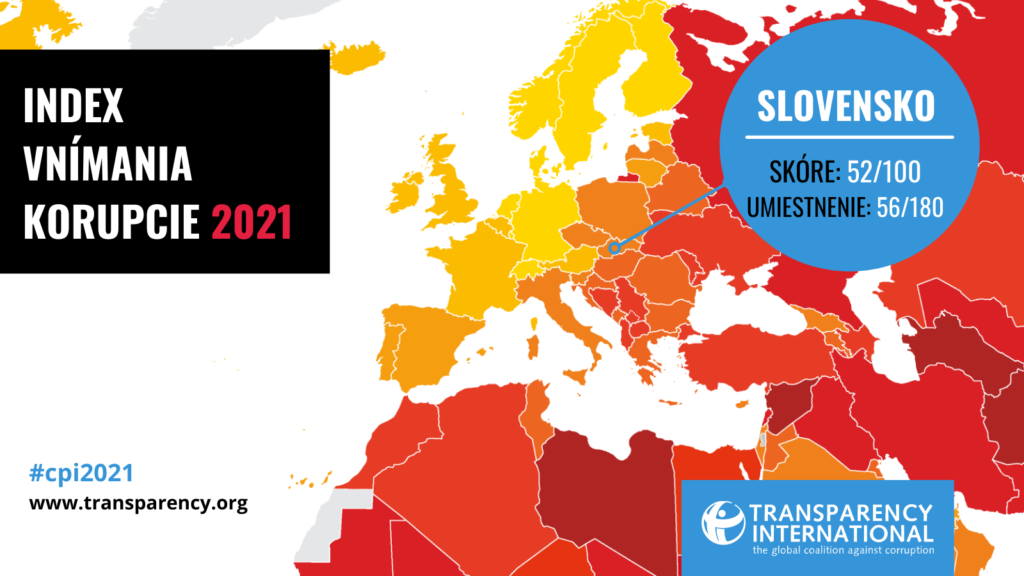

Slovakia has positively improved in the most cited corruption perception index (CPI), which is compiled annually by Transparency International, and finished in 56th place out of 180 evaluated countries. The final position for 2021 is thus improved up to four places compared to the previous year. Slovakia has also recorded a positive shift in the achieved score, which increased year-on-year from 49 to 52 points out of a hundred possible. It is thus one point higher than our current maximum (the higher the score, the less corruption).

The visible contemporary improvement can already be attributed to the current governmental and institutional action. Last year’s decline was largely an effect caused by the actions of the previous Peter Pellegrini’s cabinet (Smer, today Hlas). The perception of corruption ranking is calculated from the results of indices of various institutions, which is reflected yearly or in the merit of two years, aiming to reflect corruption from the point of view of entrepreneurs, investors or experts.

The positive improvement of Slovakia can be seen particularly in the increased efforts of the police and the prosecutor’s office in revealing and pursuing corruption. In 2021, the investigation of the cases of long-time untouchable and influential people proceeded, including oligarchs such as Jozef Brhel and Miroslav Výboh, or the former Minister of Finance and current Governor of the National Bank Peter Kažimír. The first cases have already been brought to court, while the former special prosecutor Dušan Kováčik has been convicted – although the judgement is not final yet – from abuse of office and from the act of bribery.

The increased initiative is also confirmed by the current crime statistics conducted for 2021, according to which the prosecutor’s office has so far never been prosecuting corruption more frequently (252 people last year).The overall impression is however partially disrupted by the controversial and insufficiently communicated decisions regarding the cancellation of certain prosecutions and accusations by the Attorney General, Maroš Žilinka or even by the disputes between some police services and the prosecutor’s office.

Where is space for improvement?

Since the last election, allegations of corruption and also demonstrations of the idea of Slovakia being an abducted state have appeared less frequently. Some progress can also be seen in the implementation of anti-corruption measures, although the government has so far managed to follow through only on a fraction of its own promises in this regard. Among goals reached last year is launching the new Whistleblower Protection Office and the Supreme Administrative Court, which has also taken over the agenda related to violations of the right to information or disciplinary proceedings.

Open Selection procedures have been held in several important institutions, which have brought a qualitative shift away from the long-standing practice of political nominations. Unfortunately, the government’s approach in this area has not yet been systematic, and in the previous year we witnessed several party nominations or likewise failed selection processes.

The government’s intention to exclude contracts worth up to one billion euros from public scrutiny seemed as a very disturbing aim. However, this has been eventually prevented, thanks to the rise up of the third sector and the public, and a compromise has been reached.

Last year saw a somewhat tentative start-up of important changes from the court map to the Information Act and the Criminal Code, depoliticization of the election of the director of RTVS to the settlement of conflicts of interest and insufficient property declarations of public officials. Specific changes in the legislation on verification of the property origin, material responsibility of public officials or lobbying are still in remote future.

The EU average is still a great distance

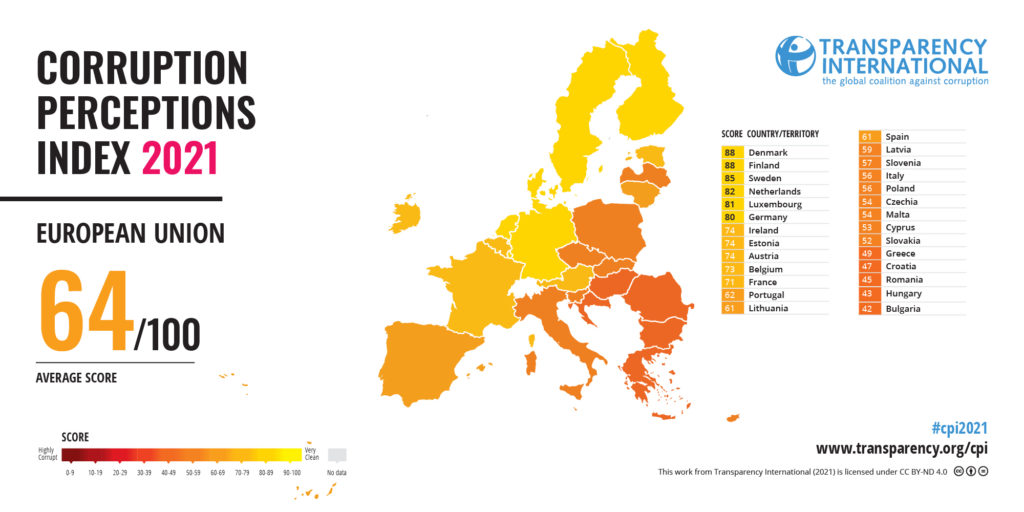

Despite the improvement, we still lag significantly behind the average of the European Union countries (average score 64). Out of the 27 states, only Greece (58th place) finished behind us, which we managed to overtake again after a year, and also four other states: Croatia (63rd), Romania (66th), Hungary (73rd) and Bulgaria (78th).

In the meanwhile, the ambition of the coalition taken from the government’s program statement to make Slovakia move up in the ranking by 20 places, compared to its position before the elections remains elusive. In order to gain on the current level of Latvia (36th place), Slovenia (41st) or Poland (42nd), we would need to get 4 to 7 more points. We still lag behind the Czech Republic by seven positions and 2 points (49th).

Additionally, concerning the development in the investigation and punishment of corruption, the decisive factor for the future placement of Slovakia in the following rankings will also depend on whether the coalition marked by quarrels will succeed in finding the majority of votes regarding the implementation of the fundamental changes. With the election approaching, it may be even more demanding than ever before.

The development in the world

The present ranking, which monitors the situation during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, confirms global stagnation in fighting corruption. In the previous year, 27 countries achieved their worst result in history (including Hungary). In the longer-term merit, when comparing the current score with the one from ten years ago, we can talk about stagnation or even deterioration in 86 percent of countries (Slovakia currently has 6 points more than in 2012).

Denmark and New Zealand managed to maintain their first place in the index (identically as last year, with 88 points) and were joined by Finland. Belarus recorded the largest drop in the score in between years (up to 6 points). The last, 180th place belongs to South Sudan with 11 points. Somalia and Syria finished ahead of South Sudan with 13 points.

The Covid-19 pandemic has served many governments around the world as an instrument for strengthening their power and restricting the right to information and as well other human rights. At the same time, many countries from the top of the ranking did not avoid problems either, as shown, for instance, by the leaked documents of Pandora Papers, which revealed extensive property hiding and money laundering through tax havens.

What does the CPI index reflect?

The Corruption Perceptions Index has been compiled by Transparency International since 1995, with current results being comparable year-on-year since 2012. The ranking is calculated based on countries’ results in 13 different indices of independent institutions, including the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, as well as consulting companies and think tanks. However, Transparency International is not involved in creating any of them.

The current result of Slovakia is based on the evaluation in 10 indices (which is also the maximum number for one country), the improvement can be seen in up to six of them. Slovakia has observed the biggest shift in the competitiveness comparison by the Swiss Institute for Management Development (IMD), in the IHS Global Insight business environment assessment and in the German Bertelsmann Foundation’s transformation index.

The evaluation thus mainly reflects the perception of corruption by managers, investors as well as by Slovak and foreign experts. In contrast to Eurobarometer opinion polls, the aggregate CPI index thus more closely reflects developments in the area of large-scale corruption (misuse of public functions and resources, purity of tenders, anti-corruption actions of the government, etc.). Details on the ranking methodology, as well as its complete results, can be viewed on the Transparency International headquarters website.

If you have any further questions, you can also contact the Slovak branch of Transparency International.

Michal Piško, Director of Transparency International Slovakia