The new electoral rules mark a noticeable step forward as regards the control of political parties financing and the purity of political life, the then Minister of the Interior Robert Kaliňák assured the public after their adoption in 2014. The introduction of transparent accounts has been particularly successful in bringing the promised improvement. However, after eight years and a half, the state administration is still failing to fine-tune these rules in a way to serve their purpose, which can be seen in numerous problems occurring in each subsequent electoral battle. Some aspects of control actually even worsened during the most recent elections held in autumn 2022 when we voted our representatives for local and regional governments.

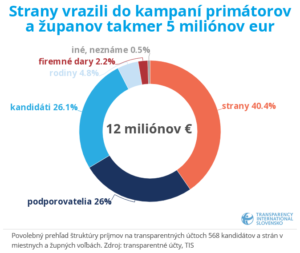

Last year, candidates for mayors, regional governors and members of municipal and regional parliaments invested an estimated total of €12 million into their campaigns. It is the second largest amount over the recent years spent on electoral campaigns, which is only exceeded by political parties’ expenses (roughly twice as big) on persuading their voters in 2020 parliamentary elections.

The electoral legislation requires all incomes and costs related to campaigns to flow exclusively through transparent accounts so that the public can precisely see from whom each candidate has received financial support as well as how much, to whom and for what they paid during their campaigns. But was is really the case?

Lost in party accounting

Let us start with a less problematic side of the problem, which is income. Even if we leave aside unlawful cash deposits or large deposits by the candidates themselves who theoretically could have received the money just from anywhere, it is true to say that political parties have also helped to hide the origin of various contributions. This has been clearly exposed when the chairman of KDH (Christian Democratic Movement) Milan Majerský let slip in an interview for Denník N daily that the party’s account had also been used to channel money from an unknown sponsor into the campaign of Rudolf Kusý running for the mayor of Bratislava as the party’s candidate. It was later found out that the donor had been Rudolf Hrubý from the company ESET who had donated €25,000 to the movement for Kusý’s campaign.

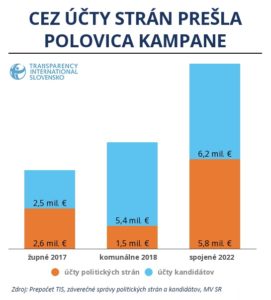

However, party accounts have turned out to be a far more complex problem in terms of public control. Some candidates have decided to use the option offered by the election law to cover the whole of their campaigns only from accounts of their parties. While in the previous regional and municipal elections only one third of campaign money altogether flowed through political parties’ accounts (4.1 out of 12 million euros in total), this time it was already one half (5.8 out of 12 million euros).

But the parties’ accounts have, with a few exceptions, merged campaign expenses of their candidates together. It was therefore impossible to identify receipts and expenses of individual candidates. Some of the largest campaigns even almost entirely escaped the public scrutiny. This was in particular the case of the sitting president of Trnava region Jozef Viskupič and the sitting president of Žilina region Erika Jurinová, both from OĽaNO (Ordinary People and Independent Personalities), but also of the above-mentioned multiple party candidate Kusý, running for Bratislava mayor, or the chairman of KDH and president of Prešov self-governing region Majerský. This strategy has also been largely used by candidates of the extremist parties Republika (Republic) and ĽSNS (People’s Party Our Slovakia).

According to the law, the obligation to conduct a paid campaign by means of a transparent account applies to all candidates for the posts of regional governors, mayors of cities, municipalities as well as city districts of Bratislava and Košice that have more than 5,000 inhabitants. There are currently 167 local administrations in Slovakia fulfilling this criterion, including the eight self-governing regions. Altogether, there were 708 politicians seeking voters’ support (76 in regional and 632 in municipal elections).

In more than 160 cases we were not able to find their transparent accounts, the reason being mostly the fact that their campaign was run by means of their parties’ accounts. We have, however, also come across some independent candidates or miniparty candidates who did not use any transparent account at all and thus it seems they skipped the obligation for paid campaigns.

Double standard for limits

Low transparency and obscuring campaigns of individual candidates has not been the only problem with political parties’ accounts. Their use has introduced two kinds of thresholds for electoral campaigns, which has reduced the overall fairness of elections.

The electoral legislation has set out strict limits for independent candidates. Candidates for regional governors as well as for mayors of Bratislava and Košice had to keep their expenses below €250,000, for other regional capitals the threshold was €100,000. Limits for smaller local administrations were lower depending on the size of their population, with the lowest level of €2,000 for municipalities with less than 2,000 inhabitants.

For parties campaigning for the benefit of their candidates, the limit has been raised to €1.5 million as a result of joining municipal and regional elections and amending the law. It is up to each political party how they distribute money among their candidates’ campaigns. Several candidates have thus managed to exceed the set limits.

This could be most prominently seen in the fight for the post of Bratislava mayor where both leading candidates exceeded the limit of €250,000. Both stood as party candidates and did not have their own transparent account. The mayor Matúš Vallo, who has retained his post, carried out his campaign through the account of his new party Team Bratislava, while his challenger Kusý even used three party accounts (Dobrá voľba (Good Choice), Sme rodina (We Are Family) and KDH).

And how much did their campaigns eventually cost? Contrary to the situation with independent candidates who must also submit individual final accounts, it is hard for citizens to find out this piece of information. Moreover, it is not possible to automatically retrieve this information from transparent accounts of political parties because, as mentioned above, campaigns of individual party candidates are merged together.

However, the team of Matúš Vallo in reaction to our criticism of such practices publicly declared that the party account of Team Bratislava would be almost solely used to finance expenses related to the campaign of Bratislava mayor. After the elections they specified that there had only been two expenditures amounting to EUR 3,000 for the benefit of other candidates. After deducting these we get to the final amount of Vallo’s campaign: EUR 358,000, making it the most expensive campaign in these elections. Also included in that amount by Team Bratislava were EUR 77,000 that had been used for their pre-campaign when the new regional party was building its brand name.

While the account of Team Bratislava has been rated by us as one of the most transparent accounts with detailed descriptions of both incomes and expenses, the situation was quite different with Vallo’s counter-candidate Kusý where we only could monitor the total amount spent on his campaign. The reason was that parties Dobrá voľba, Sme rodina and KDH funded his campaign by means of large payments to the agency Temper Communication seated in Prague that Kusý had hired. Any closer information was kept hidden within this agency, making the campaign practically uncheckable. It is a classic example of how rules can totally fail – they do require transparent accounts but do not set the quality of their administration.

Surprisingly, campaign expenses went on rising even after the elections had finished. The media shared information that the agency used by Kusý sent some additional invoices to his parties and Dobrá voľba actually did pay additional €41,000 invoiced after the elections. Kusý’s campaign has thus jumped from pre-election €292,000 to €333,000.

Three months after the elections we still do not know if this is the final amount. While the law sets a strict requirement to run campaigns exclusively through transparent accounts, these post-election extras have been paid outside such accounts. The lack of transparency in Kusý’s campaign is aggravated by the already mentioned undisclosed donors making their contributions via the account of KDH, which is currently even under police investigation.

Guessing the top campaigns

While Vallo’s and Kusý’s campaigns can definitely be considered as the biggest campaigns, it is not that easy to put other top campaigns in descending order. As described above, these efforts are hindered by the fact that several major campaigns were conducted through non-transparent party accounts. We have counted as many as seven party-run campaigns among the top 15 players.

It is quite problematic to quantify what can possibly be regarded as the largest campaign in the area of self-governing regions, i.e. the campaign of the president of Žilina region Erika Jurinová mentioned above. It is not possible to distinguish her expenses on the common party account of OĽaNO, however, the movement representatives specified for us during the campaign period that her campaign was being financed through a Žilina advertising agency called JM create. If we count all unspecified payments towards this agency on their account as well as all expenses with notes related to Žilina region, we come to the amount of €257,000. If this amount was really the total costs for the campaign of Žilina regional governor, it would mean that she exceeded the €250,000 limit for independent candidates.

We have come across similar problems in the case of another regional governor for OĽaNO: Jozef Viskupič in Trnava. Payments to the agency Citadela that was in charge of his campaign and other expenses with an indication of Trnava region equal to €204,000. His campaign would thus take seventh place in the ranking. In both cases, the movement has not confirmed if these are real campaign expenses of these political figures.

A similar situation can be described in relation to the campaign of the chairman of KDH and president of Prešov region Milan Majerský. It is again impossible to separate costs for his campaign from other expenses on the account. KDH has only informed us that they spent EUR 219,000 in total for their campaign in Prešov region. We can only guess if this amount is solely for the promotion of Majerský or if it also includes other party candidates.

Bad practice of big players

Campaigns run by both regional governors for OĽaNO and the chairman of KDH can thus, together with Kusý’s campaign, be regarded as the least transparent.

The campaign of the president of Bratislava region Juraj Droba proves that things could be done differently for party candidates. Although this candidate did not have his own transparent account either, his party SaS (Freedom and Solidarity) did mark out all his expenses on their party account and in the end, they were also willing to provide information about overall costs of his campaign (€125,000).

Even the opposition party Smer (Direction – Slovak Social Democracy) showed better practice when its two major candidates – the president of Trenčín region Jaroslav Baška and the challenger of Erika Jurinová in Žilina, Igor Choma – had their own transparent accounts where they were entering a part of their campaigns. Unfortunately, we again do not know all their expenditures and cannot assess the grand total.

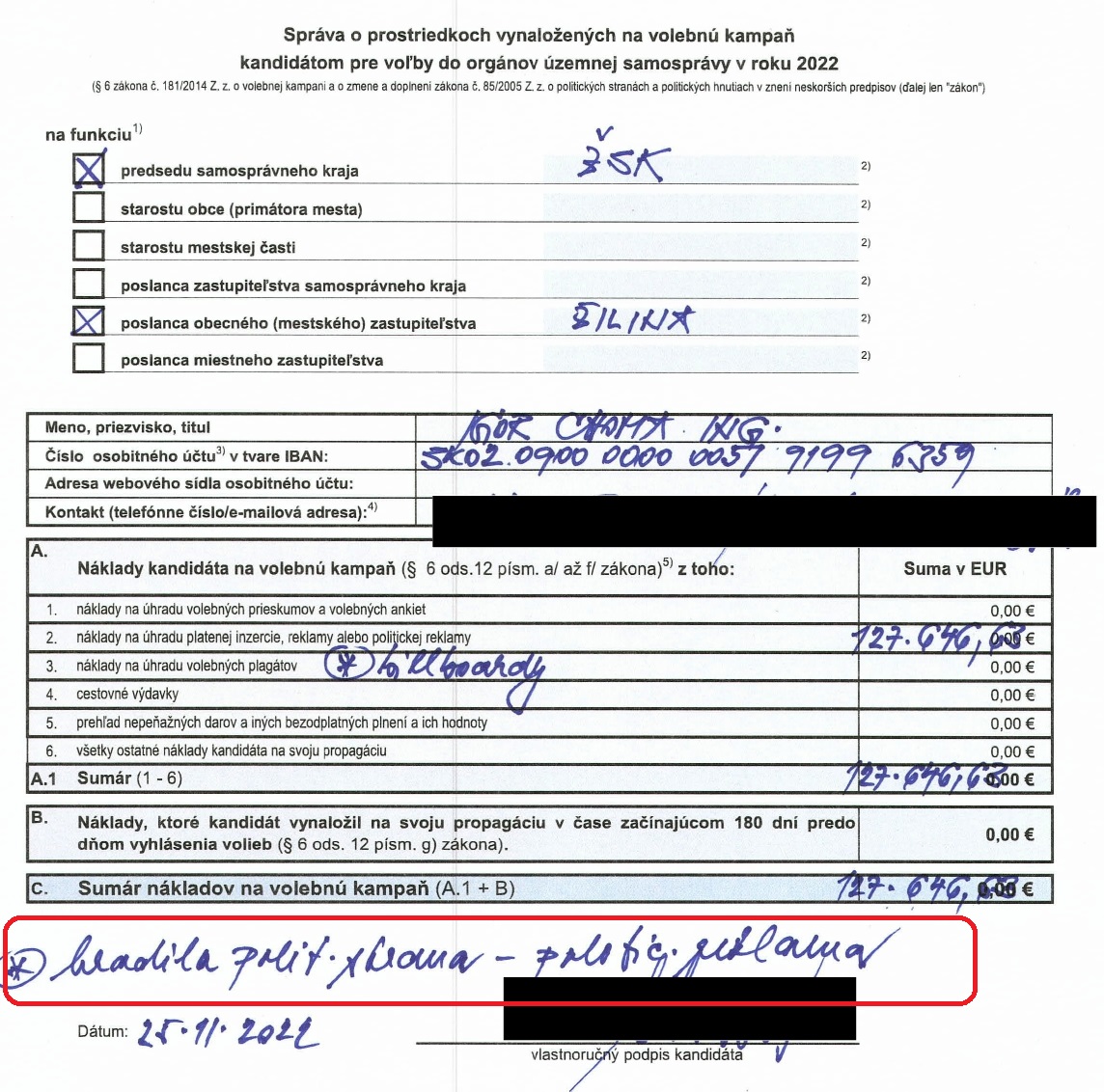

While it is true to say that Baška kept clear records on his account, a part of his campaign was also financed from the party account of Smer. As for Choma, his entire campaign is hidden behind six large payments to a media agency (except for payments for advertisements on a social network).

The last nail in the coffin of his transparency was his final report, where he wrote in his own hand one single amount. The former mayor of Žilina claims that the only expenses for his campaign were payments for political advertisements amounting to €128,000, saying that we should add to this amount billboards paid by the party. Yet, it is unclear how much these have cost and where other expenses of this large regional campaign are (for instance election events all across the region). It is therefore sure that the total costs of his campaign had been higher than the €128,000 he declared. The political party Smer did not answer to our questions.

Limits exceeded in Prešov

The former mayor of Prešov Pavel Hagyari who tried to return to this post with the support of Starostovia a nezávislí kandidáti (Mayors and Independent Candidates) and Sme rodina is also a specific case of combining one’s own and a party campaign. It is however not clear how much his campaign cost in total. Although his final report states EUR 60,000, his transparent account only shows expenses amounting to EUR 49,000.

The difference cannot be explained by campaign activities carried out on his behalf through the party account of Sme rodina. These expenses are in fact substantially higher than the missing €11,000. Contrary to some other political parties, Sme rodina did properly mark their expenses and according to their transparent account they spent EUR 60,000 on Hagyari’s campaign.

So in Hagyari’s case, if we count EUR 60,000 reported in his final report and the expenses of Sme rodina in his favour, the total would be EUR 121,000. This would rank Hagyari among top 15 campaigns.

He would be very closely followed in this imaginary ranking by another unsuccessful candidate for the mayor of Prešov Ľuboš Micheľ. The former football referee stood for election as a candidate for Hlas (Voice – Social Democracy) but he carried out his campaign on his own. However, he failed to comply with the financial limit of €100,000 applicable for the third largest city in Slovakia, which could also be seen on his transparent account. This candidate acknowledged it in his final report as well, where he quantified his total costs to €103,000, and will probably have to face a fine.

There were questions arising in connection to Micheľ’s campaign already during its progress, because in a great majority of his expenses there were no data on their recipients on his transparent account. He even made cash withdrawals from his account and there were also several substantial refunds.

Micheľ’s final report is also quite dubious, as he declares therein costs for election posters worth EUR 6,853. However, according to data received by Transparency from the research agency Kantar that has been long monitoring the advertisement space in Slovakia on commercial basis, Micheľ had a total of 111 advertisement sites from five billboard companies that are available for price list rates of EUR 40,000. It is not very likely that he could have negotiated prices six times lower with these companies.

By the way, checking the reality of expenses on outdoor campaigns remains one of the most significant weak points in public scrutiny. Candidates are seldom willing to share details on their billboards and it is not possible to identify these expenses on transparent accounts because they are included in large overall payments to agencies. There is no way to find out more specific information in final reports either, because the outdoor is hidden in a wider group of “costs for election posters”.

The environment of billboard companies also continues to be non-transparent. A number of them have refused to provide concrete data even to Kantar agency, in other cases the data is incomplete or based only on price list rates without discounts.

Confusion in Košice as well

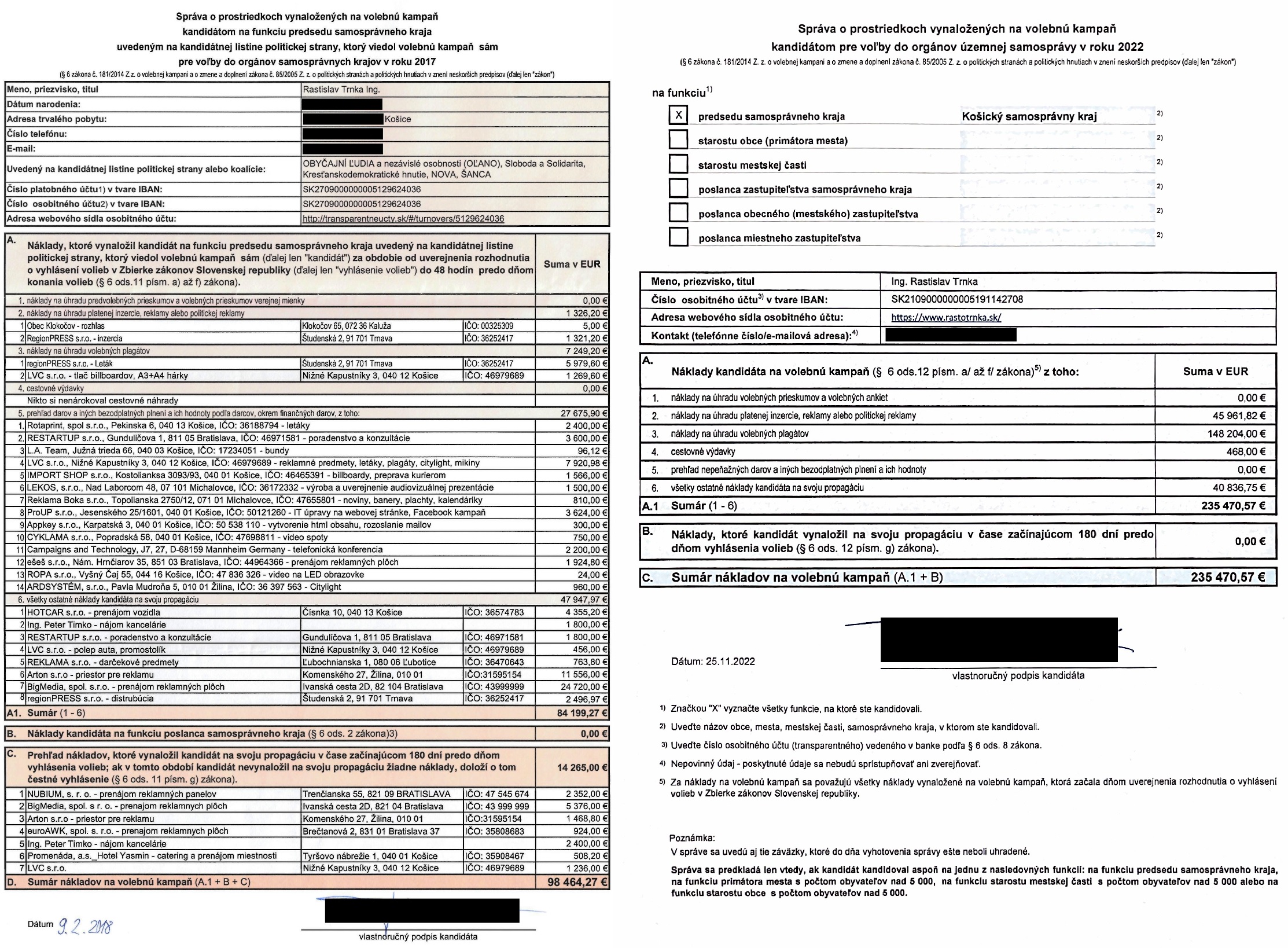

In Košice region, its president Rastislav Trnka (KDH, Aliancia (Alliance), Starostovia a nezávislí kandidáti, Šanca (Chance), DS (Democratic party)) has managed to keep his post. In 2017, he was successful also thanks to his anti-corruption rhetoric. This was also demonstrated by his final report that beat the set standards, as his campaign was detailed into 44 lines instead of compulsory 7 lines.

However, he was not acting as transparently now as last time. In the beginning of summer the whole region was full of his billboards, he was publishing videos and pouring money into online advertisements. Yet, his transparent account was empty. Later it started to show his expenses but again, significant expenditures were kept hidden under payments to agencies, which prevented the public from controlling the fourth biggest campaign. Trnka’s current final report is now limited to minimum legal requirements.

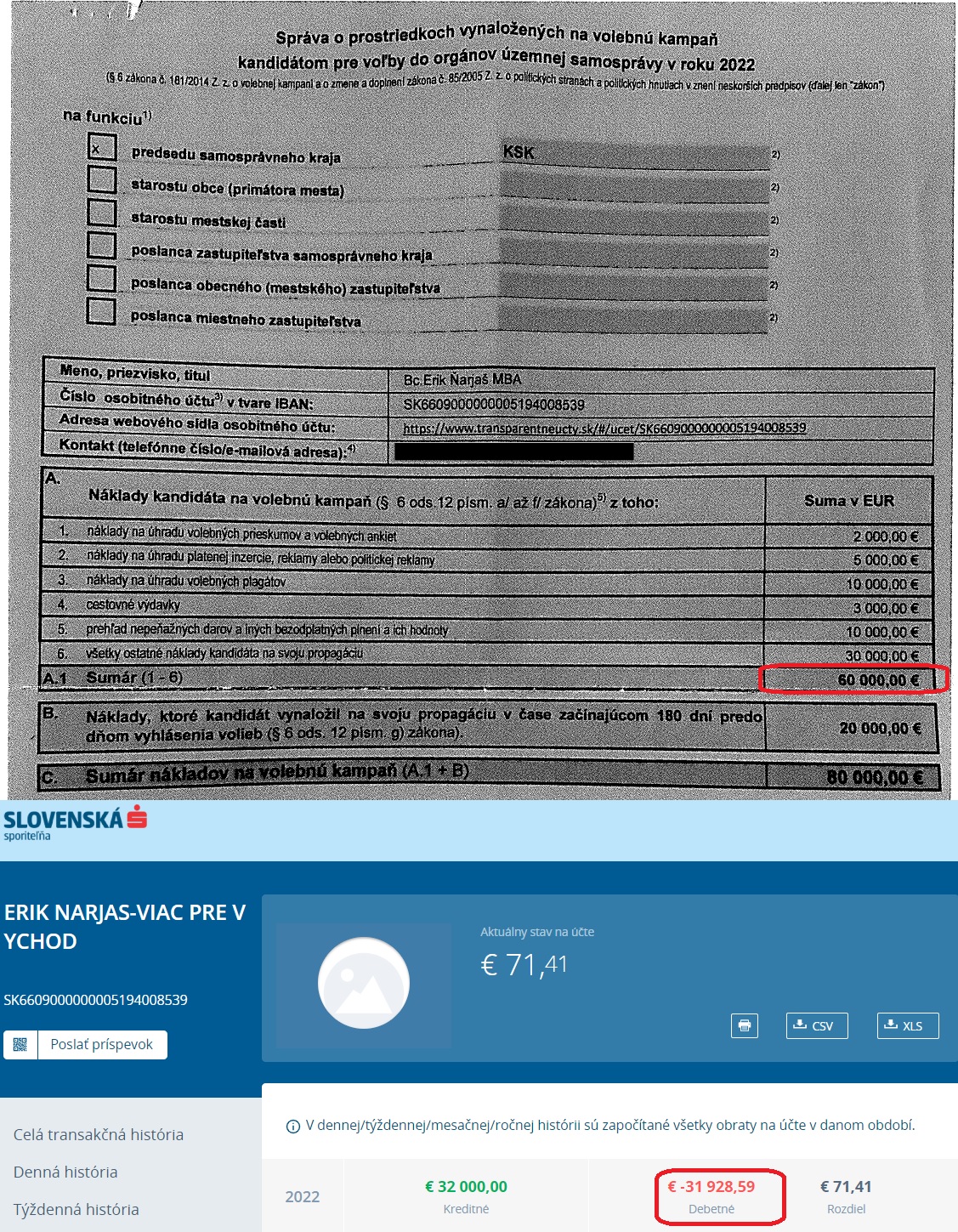

Another campaign raising doubts is the one run by Trnka’s unsuccessful challenger Erik Ňarjaš from OĽaNO who has been recently appointed for board member of TIPOS (state lottery company, transl. note) by his party chairman Igor Matovič shortly before the latter resigned from the post of finance minister. Ňarjaš rounded off all data in his final report to the nearest ten thousand. He quantified his official campaign at €60,000 (plus 20,000 euros for pre-campaign). But his transparent account only shows expenses amounting to less than €32,000 and it is not clear where the remaining half of the campaign is.

In his final report, Ňarjaš declares that his billboard campaign cost him €10,000. However, his transparent account contains expenses for billboards for almost €20,000 from various outdoor companies. Data from Kantar agency even indicate that he hired 184 advertising sites from five billboard companies for a list price rate of €45,000.

Lack of transparency with political parties as well

Among party campaigns, the parties that invested the most in these regional elections were OĽaNO and Sme rodina, both exceeding one million euros. These expenses, however, also included billboard campaigns of these governmental parties unrelated to elections (EUR 200 per child, public rental housing).

The movement OĽaNO was particularly limping along with its transparency, as they started their campaign with large aggregate payments to agencies and only corrected this inappropriate practice in the second half of the campaign. As explained above, huge regional campaigns of the party’s candidates Erika Jurinová and Jozef Viskupič are almost entirely obscured in agency payments and the bank accounts give a very little clue about their particulars.

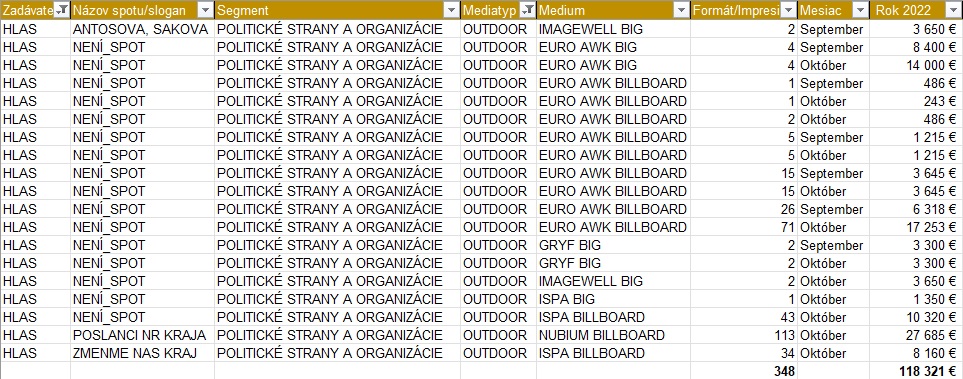

The approach adopted by the party Hlas can also be regarded as quite problematic because they reported only €135,000 of campaign expenses. Data from monitoring of political advertisements that we have received from Kantar agency suggest that in reality the campaign might have been more expensive.

Kantar has monitored 348 outdoor hoardings that were hired in September and October by Hlas and estimated the value of these ads to be EUR 118,000. But the amount stated in the final report of Peter Pellegrini’s party is different: EUR 19,642. Even if we take into account possible price reductions against price lists, it probably is still several times less than the reality. The party has not explained this irregularity yet.

Lack of transparency can also be observed in campaigns of various other political parties. For instance, the party ĽSNS of Marian Kotleba did not bother marking expenses related to their individual candidates either. ĽSNS nominees ran their campaigns almost exclusively through the shared party account. In addition, this party is an another example of quite a few cash withdrawals from the account – it is absolutely impossible to find out how such money was spent.

Only one fifth of campaigns were transparent

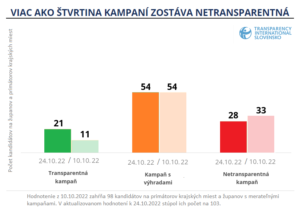

What would then be an overall summary of campaign transparency? We tried to assess the level of transparency in two occasions when campaigning efforts were in final stage in October by evaluating the most significant indicators with candidates in self-governing regions and regional capitals. We primarily focused on the quality of financial reporting of campaigns via their compulsory transparent accounts, the method of their financing, their compliance with the basic legal requirements, as well as whether minimal information for voters about the candidate in question and his/her campaign is ensured.

In the end we could rank 21 out of 103 evaluated candidates as running a “transparent campaign” (in the first evaluation, it was 11 out of 98 candidates). However, more than one fourth of campaigns had to be labelled as manifestly non-transparent, while in one half of candidates there were prevailing reservations.

Billboards keep their key role

Our unique portal volby.transparency.sk, where with the help from programmers we managed to summarise data from all transparent accounts, enabled us to analyse incomes and expenses of candidates from a wider perspective as well.

The portal collected data from 542 accounts with more than 17,000 expenditure transactions. The main finding is that despite good intentions that the transparent accounts are aimed to serve, i.e. to enhance public scrutiny of campaign funding, the reality lags behind expectations. The accounts often provide low data quality.

This becomes quite evident when trying to differentiate campaign expenses according to their type. The total of 11.5 million euros were spent altogether and as much as one third of this amount cannot be more precisely categorised either because candidates failed to properly mark recipients and expenses, or they were large unspecified payments to media and advertisement agencies as described above.

The latter amounted to EUR 2.9 million. It practically means that this money just flowed through the accounts of political parties and candidates into the obscure environment of agencies. This level of non-transparency is similar as in parliamentary elections in 2020, where according to our estimates 6.3 out of 23.6 million euros were poured to agencies.

As for the remaining two thirds of expenditures that we were able to clearly identify based on meaningful transaction descriptions or the specific focus of receiving companies, the largest portion of money went to outdoor advertising. Candidates invested at least EUR 2.6 million in bigboards, billboards, citylights, banners and other advertising hoardings, which makes almost one fourth of all expenses. If we mathematically distributed the above mentioned third of the overall pie, where closer identification is not possible, among individual types of expenses, these outdoor sites would be increased by approximately one third of it (about 3.9 million euros).

We consider this estimate to be realistic also based on data comparison that we received from the research agency Kantar, that has been long monitoring the advertisement space in Slovakia on commercial basis. Although not all billboard companies are willing to share data on political advertisement and only price list rates are publicly known, according to Kantar’s monitoring the expenses of candidates and political parties on outdoor ads over the last four months reached EUR 3.2 million.

If we again, same as with billboards, mathematically distributed the third of unspecified transactions among other types of expenses, the outdoors advertisements (34%) would be followed by promotion materials of candidates (approximately 30%) and only then by costs for online advertisement, the latter being estimated at around 14% of total expenditures. Such distribution matches the situation during 2020 parliamentary elections where according to our findings, outdoor ads reached 38% and online ads reached 15% of overall costs (3.6 and 9 million euros respectively, out of EUR 23.6 million).

Who did pay for all this?

We have also managed to analyse incomes on transparent accounts of candidates and parties. The joint elections were specific by the large extent of using private sources for pre-election campaigns. These dominated over state finances that are available to political parties. Roughly 40% of all expenses of candidates were covered by such public finances but this package also includes other minor sources in addition to state money, such as membership contributions, loans or donations from supporters.

Roughly two thirds of financial resources used in these elections might have been private. The fact that supporters are willing to actively contribute to a political campaign can be regarded as something positive. In this light, the most convincing has been Matúš Vallo and his Team Bratislava, as they have received contributions from as many as 1,245 unique donors.

However, such big proportion of private sources also brings certain risk to the fairness of elections, as in addition to the votes cast, various hidden background interests might also have had a significant share in the success of individual candidates. It is therefore surprising that the state administration is not very interested in the income side of campaigns. Candidates even do not have to report at all on these incomes in their final reports.

There have been a number of questionable campaigns in these terms. For instance, we have pointed to the former tennis star Martin Kližan running for the mayor of Petržalka (city part of Bratislava, transl. note). Kližan’s billboard campaign has been either the most expensive or the second most expensive among campaigns conducted in the capital city (depending on the costs of outdoor ads of Rudolf Kusý, which are unknown), reaching an estimated amount of €60,000 to 80,000. However, the final report of this candidate only states billboarding for less than €23,000.

His transparent account shows only €47,000 out of the grand total €83,000 declared in his final report. These funds were deposited solely by him and a close person. He finished third in the elections, winning 8.86% of votes (2657 voters). One vote cost him 31 euros. Just for comparison, for the re-elected Petržalka mayor Ján Hrčka who spent only EUR 753 for his campaign, one vote cost him thousand times less – only 3 cents (he won 23,120 votes).

Advantage of being in office

This is another problematic aspect of fairness of elections. We have repeatedly pointed to the practice of misusing the advantages stemming from the position of presidents of self-governing regions and mayors whose campaigns often drew on public budgets earmarked for the promotion of the relevant self-administration.

In regional and municipal elections, the results in fact lie in a great number of minor battles for individual local administrations where even a few thousand euros for promotion give a substantial advantage to sitting statesmen. This is also indicated by the election results. Mayors of 71% out of 2,904 municipalities where elections had been held succeeded in keeping their office. If we limited our consideration only to those mayors who ran for re-election, their rate of success was overwhelming. As many as 86% of them managed to defend their mandate, which is even slightly higher number than last time.

Convincing success of sitting municipality leaders largely testifies to the results of their work. However, it is no doubt that the possibility to benefit from their current position when running for re-election was another and equally apparent reason of success of many of these mayors. The above mentioned case of Ján Hrčka, the mayor of Petržalka, is an extreme example of this situation. In 2018 he needed a campaign worth EUR 48,000 to win this important self-administration position, while in 2022 less than one thousand euros was enough for him to defend it.

Before all campaigns started we had brought to the attention increasing budgets for municipal and regional public newspapers that are delivered to mailboxes of people living in relevant areas. For instance, one year before the elections Bratislava raised the number of copies of its monthly newspaper from 36,500 to 192,000. And Košice regional administration increased the circulation of its monthly to 330,000 copies in the year of elections, making it the most expensive local administration periodical with costs amounting to EUR 340,000.

The ranking of newspapers published by one hundred largest towns including self-governing regions that we carried out last year, has shown persistent problems with impartiality. During the pre-election period, many municipal newspapers dedicated yet more space to uncritical celebration of achievements of sitting mayors and regional governors. This was again confirmed in our evaluation of pre-election issues of newspapers published by Bratislava city parts. We had reservations in terms of fairness in one third out of 12 evaluated titles.

The state control is rather underwhelming

Months-long monitoring carried out by Transparency has highlighted many errors and concrete problems in public control as well as tepid interest of the state in law enforcement.

Dozens of candidates have failed to comply even with the basic obligation to notify the Ministry of Interior of their transparent accounts during their campaign. Moreover, data exports from paid statuses of candidates in self-governing regions and larger cities have confirmed a widely used practice of disregarding the legal obligation to provide information on the advertiser and the supplier with such content. This information was missing almost in every other political advertisement.

The global ban on third parties has led to breaches of law or pushing campaigns to a grey zone. Several anonymous anti-campaigns have again appeared across Slovakia, e.g. the one in Nitra. Despite our complaint to the Ministry of Interior, there is still no answer to the question if the billboard, that lacked proper information about the advertiser and was thus in breach of the law, was the work of one the mayor’s counter-candidates or it was an initiative of citizens who are not allowed by the current legal text to pay for a billboard in a campaign.

Ignoring the law even continues after the elections, as several candidates have not submitted their final reports to the ministry. For instance the report is missing in case of the mayor of Rožňava Michal Domik or candidates for mayors of Komárno, Košice and Michalovce Ildikó Bauer (Aliancia), Jozef Karabin (independent) and Miroslav Dufinec (Smer, Sme rodina, SNS (Slovak National Party), SMS (Party of Modern Slovakia) respectively.

We have informed about more than fifty findings related to problematic aspects of campaigns or directly to breaches of the law in our portal volby.transparency.sk. These as well as other considerations have served as the foundation of our basic recommendations presented in the final part of this summary analysis that we believe can contribute to greater transparency and fairness of electoral battles.

Ten improvements for fairer elections

⦁ Level playing field for candidates of political parties and independent candidates

Party candidates should be subject to the same requirement as independent candidates to have a transparent account of their own when conducting a campaign.

⦁ Taking into consideration the existence of regional political parties

The electoral legislation should distinguish, at least in terms of election expenditure limit, between regional political parties running their campaigns only in the territory of the relevant regional administration and political parties running nation-wide campaigns. The limit should be lower for the regional ones.

⦁ Reconsidering financial limits

The limit for political parties was increased before the elections (from €500,000 to €750,000) but eventually, other thresholds turned out to be tight: The €100,000 limit for campaigns related to mayorship in big cities and the €250,000 limit for the mayor of the capital city, as both have been exceeded using a legal gap.

⦁ Rules on transparent accounts

Transparency of electoral campaigns can be significantly increased by introducing rules on how transparent accounts should be kept, especially with a ban on large aggregated payments to agencies. There should also be a precise, pre-established method of describing incoming and outgoing transactions that would be binding for all candidates.

⦁ More detailed final reports

Final reports should be made more clear. It would be appropriate to add at least expenditures for online campaigning activities. Final reports should also be more extensive. There is currently no obligation to report on the structure of incomes within a campaign.

⦁ Better regulation of both outdoor and online campaigning

Define more in detail conditions of political campaign in online environment as well as the obligation to state the advertiser and the supplier of such advertising. These should also apply outside the official election campaign period. Impose on billboard companies an obligation to report data on political advertisements during an electoral campaign.

⦁ More active surveillance of compliance

Create an independent body to oversee the elections and funding in politics or at least ensure that the state committee is not mainly comprised of members appointed by political parties. In the latter, independent personalities with moral and professional credit should be given space, promoting the law and not the interests of political parties.

⦁ Reducing advantages stemming from the position of sitting presidents of self-governing regions and mayors

Introduce rules for the operation of regional and municipal public media as well as a ban on conducting a campaign using local administration media channels, which should also apply to profiles of leading politicians on social media.

⦁ Reintroducing third parties in a regulated manner

The current electoral legislation set-up only allows candidates alone and political parties to carry out a campaign. This amendment has eliminated the problematic practice of circumventing thresholds set for candidates by means of third party supporters. However, at the same time it has pushed all civic initiatives to the advantage or disadvantage of candidates to the wrong side of the law or to the grey zone.

⦁ Transparent accounts for referendums as well

Despite all objections and reservations, the public scrutiny of the campaign related to the autumn regional elections was incomparably greater than the control of the ⦁ referendum on the possibility to shorten the standard electoral term, held in January. Transparency of referendum campaigns is not subject to regulation and should there be future amendments to the election law, it would be a good opportunity to fix this bug as well.

Ľuboš Kostelanský, Michal Piško

If you believe it is important to control funding of political parties and monitor the fairness of campaigns, you can support our work too. You may make direct contribution or donate 2% of your paid tax. Thank you!