Bratislava, 25 September 2023

OĽaNO and their coalition partner, the Christian Union, fell into the category of non-transparent campaigns, shared with Smer, in the repeated assessment by Transparency International Slovakia.

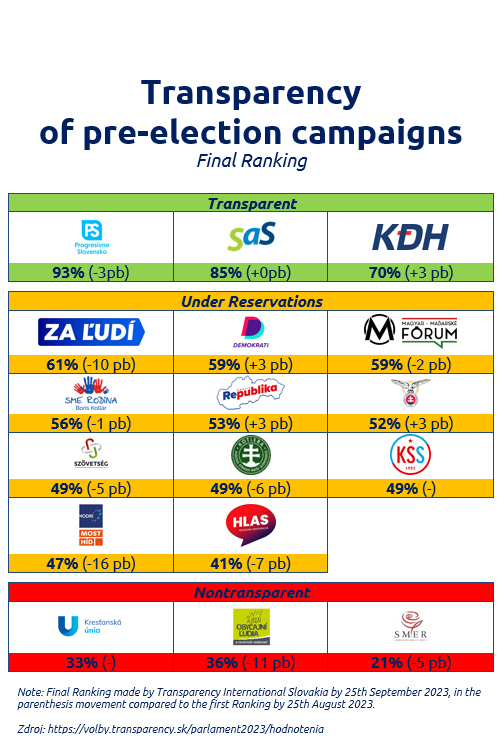

A few days before Saturday parliamentary elections, most parties have problems with campaign transparency. In the final evaluation made by the anti-corruption organisation Transparency International Slovakia, only three parties were awarded the “transparent campaign” grade: Progresívne Slovensko (PS – Progressive Slovakia), Sloboda a solidarita (SaS – Freedom and Solidarity) and Kresťansko-demokratické hnutie (KDH – Christian Democratic Movement). At the other end of the ranking, OĽaNO (Ordinary People and Independent Personalities) and its coalition partner Kresťanská únia (Christian Union), whose campaign has grown significantly in recent weeks due to high spending on the electoral newspapers of the three-party coalition, have joined Smer (Direction – Slovak Social Democracy) in the category of “non-transparent campaigns”.

Currently, Transparency has included 17 of the 27 entities standing for election that run campaigns exceeding €50,000 threshold and that have at least 10 major spending transactions in their accounts. Thus, in addition to the Christian Union, the Communist Party of Slovakia is also a newcomer to the ranking. All in all, 11 parties were rated as having a “campaign with reservations”. Only three entities improved their ratings in the campaign finale, while the rest stagnated or even worsened. The drop concerns in particular the campaigns of Modrí, Most-Híd (The Blues, Bridge) (-16 percentage points), the OĽaNO movement (-11 pp) and Za ľudí (For the People) (-10 pp).

Thus, the considerable differences in campaign transparency between the different players widened even further in the tail end of the campaign. Progressive Slovakia and SaS still run the most transparent campaigns, which are itemised in detail on their transparent accounts, including their pre-campaigns. However, the organisation has some reservations about these too. PS continues to purchase outdoor campaign materials through bulk invoices from a non-transparent billboard company, and Transparency has also noted a failure to return a small cash deposit, which is not allowed by law. Large agency payments are also increasingly used by SaS.

KDH has managed to move into the highest category also thanks to the fact that it abandoned the practice of using larger advance payments, which make the real course of the campaign less transparent. The party Za ľudí has failed to stay among the best even after its leader Veronika Remišová decided to follow the example of Michal Šimečka and filled out an extended asset declaration for Transparency.

The transparency of its small campaign has worsened due to a large agency payment to buy TV advertising for the aforementioned three-party coalition in which the party is running for election, but also due to the failure to return cash donations. Another public figure providing enhanced asset declaration for Transparency has been the chair of Piráti (Slovak Pirate Party) Zuzana Šubová, but this party is not part of the evaluation as their campaign costs are low.

During the current electoral campaign, we may actually witness breaking the 3-million spending limit for one party for the first time. The OĽaNO movement took advantage of a loophole in the law and did not include in its campaign €800,000 spent on the purchase of 79 antique Fiat 500 cars that they use as part of their campaign. Another problematic fact in the case of Igor Matovič’s movement is that a large part of their billboard campaign, paid in advance before the official start of the campaign, is missing from their transparent account too.

Smer, a party aspiring to win the elections, also runs a non-transparent campaign. A few days before the elections, Robert Fico’s party has the highest expenditure of all – up to €2.5 million. The party has already funnelled over four fifths of that money from the transparent account through large aggregate payments to its own agency. Thus, the public cannot check the credibility of the spending in practice, or whether the party has covertly exceeded the 3-million spending threshold, to which the party got very close in the last elections.

“Voters too are aware that a non-transparent approach before elections can be a problem afterwards. More than half of respondents of the representative survey conducted by IPSOS agency for Transparency in mid-August agreed that if a party or politician acts unfairly in a campaign, they will continue to do so after being elected,” notes the organisation’s director Michal Piško.

One week before the elections, the spending on transparent accounts already exceeded €19.5 million. Together with the invoices for the end of the campaign and the expenditure from the pre-campaign (before 9 June 2023), Transparency estimates that the final amount will surpass the 2020 record, which has been the most expensive campaign so far (€23.6 million). This time, up to 12 parties could invest over a million in their campaigns, with seven of them possibly exceeding two million. The recent analysis of nearly 9,000 spending transactions in transparent accounts shows that, with unspecified payments divided among categories, parties have so far spent about a third of the amount on outdoor advertising, a fifth on promotional materials, about a sixth on online promotion, and less than a tenth on campaign events.

Yet, up to half of all campaign spending could be privately financed. Transparent accounts still fail to reveal all party donors, as up to 85% of revenues originate from party accounts. While some parties are not hiding their donors and creditors, for others we will probably find out after the elections or only in the 2023 annual reports.

In addition to the problems of Smer and OĽaNO, Transparency has repeatedly drawn attention to the shady financing of the campaign run by Republika (Republic), which is based on large loans to the party leaders. It is currently also unclear how the Communist Party of Slovakia is financing its campaign, which has already cost almost €200,000. In turn, the party Hlas (Voice) is approaching the €3.5 million cap on donations and loans during one election period, a limit introduced in 2019, making it harder for the party to compete with other big well-established parties. There is thus a risk of underestimating the campaign (currently at €2.14 million), which is exacerbated by the fact that Hlas is the only party that does not accept donations in the campaign through the transparent account, but only informs about them on their website.

The parties were evaluated in three categories – Transparent Account, Campaign Financing and Campaign Awareness. The aim was not only to examine compliance with the legal rules, but also see the parties’ willingness to go the extra mile for public scrutiny. For example, whether they provide clear descriptions of spending (true for 9 out of 17 parties), whether parties report on their pre-campaigns (7 out of 17), campaign teams (7 out of 17), or events (8 out of 17), as well as whether they demonstrably check the background of major donors and creditors (5 out of 17). The evaluation again included a test of willingness to communicate with voters, where only six parties answered to an e-mail question sent by the Transparency collaborator and as few as three parties answered to such a question sent via a social network.

Transparency will continue monitoring shortcomings in campaign transparency until the elections; the full results are available to the public on a special campaign portal volby.transparency.sk, including the original evaluation from August a the methodology. The results of the campaign transparency assessment are the output of a project supported by the Pontis Foundation.

For more information contact:

Ľuboš Kostelanský, lubos.kostelansky@transparency.sk, 0948/003 625,

Martina Hilbertová, martina.hilbertova@transparency.sk,

Michal Piško, pisko@transparency.sk