The topics of corruption and rule of law are also receiving more and more attention in the “alternative media”. Their impact on public opinion and the quality of democracy cannot be underestimated, as both Transparency’s unique content analysis and Focus’ representative sample survey show.

“Support the only truly independent news media,” the disinformation portal Hlavné správy urges readers. The latter supposedly defends freedom of speech against the propaganda of the “mainstream media, the liberal establishment or corporations.” Other “alternative media”, as they call themselves, use similar arguments to attract readers and advertisers. And although they will lose some of this “underground exclusivity” with the apparent sympathy of the politicians of the new coalition, there is probably no need to expect a departure from their long-established “business model”.

So how does their opposition to the mainstream media, independence, freethinking or the quality of information look like in practice and what impact does it have on public opinion? At Transparency International, we decided to take a closer look at these questions in the context of corruption scandals, the rule of law and independent institutions. These topics have been closely monitored by the Slovak branch of the world’s most influential anti-corruption organisation for 25 years.

The appeal of the alternative

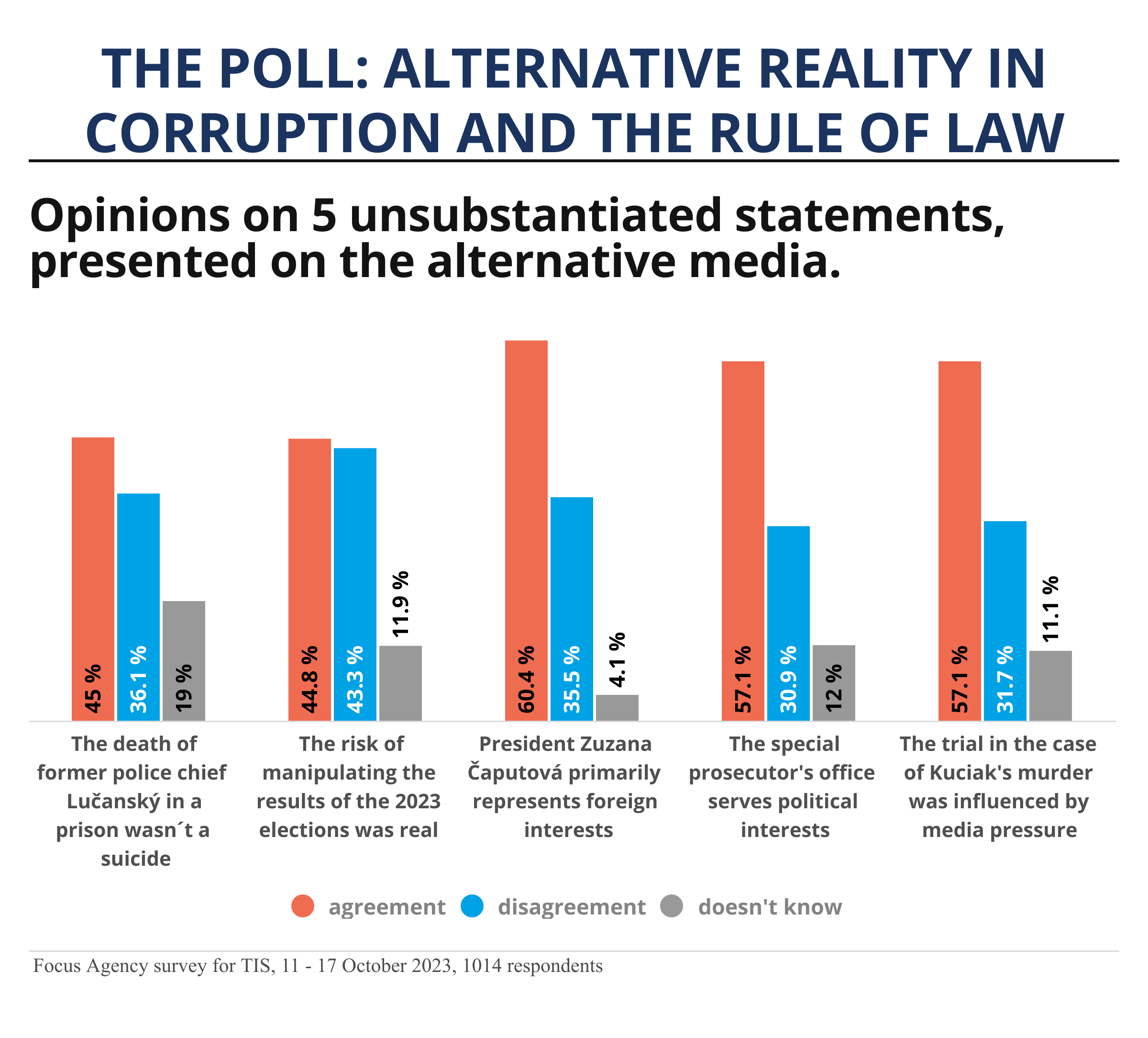

First of all, let’s start by summarizing that their interest in those topics has been growing rapidly in recent years, and this is reflected in public opinion. This is clearly indicated by a survey which Focus conducted for Transparency in mid-October. In this survey, we asked a representative sample of 1014 respondents to what extent they trusted five questionable claims concerning said topics that often appear in the “alternative media”.

Although the results of the survey were somewhat predictable, also on the basis of other sociological research, the extent of people’s tendency to believe conspiracy or at least unsubstantiated theories is nevertheless surprising. For all five questions, more people leaned towards an interpretation closer to “alternative media” (see chart above). Details of the survey can be read in a separate analysis “In regard to the corruption and law, Slovaks are attracted by alternative reality”.

These topics only became more prominent on the disinformation scene after the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová in 2018. The intensity of the revelations, detention of powerful persons from politics, business and law enforcement institutions, as well as the fierce backlash in the form of questioning the investigations or the war within the police, imported these topics into the spotlight of the “alternative media”.

It is this case and its coverage by the disinformation scene that we at Transparency have chosen as the starting point for our content analysis. We gradually added nine other key cases concerning corruption, rule of law and democratic institutions, which are analysed in detail in the study of the same name “How the alternative media discovered the rule of law and the fight against corruption”.

From the periphery to the centre of attention

The sample for the analysis consists of the online news portals Hlavné správy and Hlavný denník and the monthly Extra plus. All three are listed in the database of the Konšpirátori.sk initiative as media with questionable credibility and quality of content. However, since all the texts analysed can by no means be described as manipulations or disinformation, we have borrowed the more neutral label of “alternative media” for the purposes of this analysis. In order to describe their approach more clearly, we also included a reference sample of the so-called mainstream media represented by Aktuality.sk, Denník N and Denník SME.

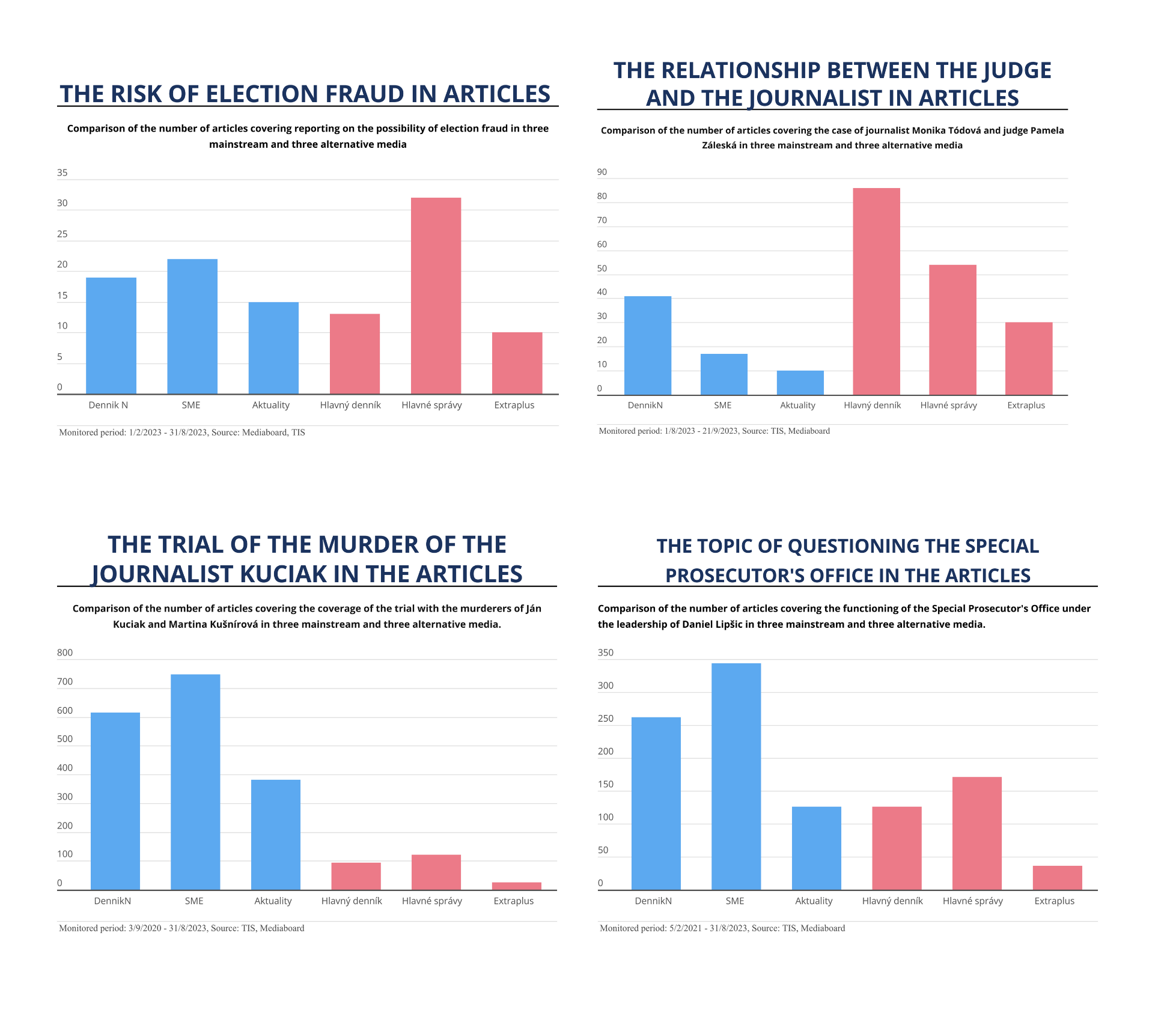

A review of the Mediaboard media archive confirms that these topics have been heavily prioritised in the “alternative media”. Despite the fact that the “alternative” sample consists of two portals that were blocked by the National Security Office decision for several months after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, their editorial staff consists of only a few people, and the relatively small magazine Extra plus is also included in the trio, the number of articles on several topics was close to the strong mainstream trio.

It substantially manifested in the case concerning the death of former police president Milan Lučanský, as well as the relationship between journalist Monika Tódová and judge Pamela Záleská, which the “alternative media” covered even more often than the mainstream media.

The murder of Ján and Martina was one of the first major topics related to corruption and rule of law that attracted significant attention from the “alternative” where conspiracies were also spread. The first trial in 2020 was covered by 70 domestic and international journalists. Since the outset, the mainstream media tried to bring important context to the case and the related matters, although sometimes indeed with problematic aspects. Uncommon for the rule of law, the mainstream also relied to an unprecedented extent on leaks from the files, and their interpretation often raised unrealistic expectations that all the defendants would also be convicted.

The “alternative media”, on the other hand, used the acquittal of the main suspect in soliciting a murder, the mafia businessman Marián Kočner, to criticise both the establishment and the mainstream media. They did not openly stand up for Kočner as he was apparently too toxic a figure for them as well. They admitted the possibility of his guilt. They saw the failure of the police and the Special Prosecutor’s Office, which is supervising the case, as the reason for his acquittal; they also suggested a conspiracy between journalists and politicians.

The paradox is that despite the massive criticism of the mainstream media in the Kuciak case and other issues of corruption and the rule of law, the “alternative media” were literally dependent on them. They hardly ever brought their own findings or investigative reporting. Instead, they published unsubstantiated theories and conspiracies, disputed facts with questions, or commented on information brought by someone else. Neither Hlavný denník nor Hlavné správy have hesitated to copy entire passages from articles by other journalists, including those they criticise by name.

One of the reasons why the “alternative” cannot compete with the mainstream with its own production may be the absence of journalistic methods of work. They do not uphold the Code of Ethics of the Slovak Syndicate of Journalists, nor do they adhere to the basic standards of journalism, such as balanced reporting, impartiality or fact-checking. Published reports are often unverified, without giving the possibility to respond, even if they publish serious accusations.

Victims of “monster trials”

A number of corruption topics have become interesting for the “alternative media” only later. The most prominent was the Búrka case (Storm), considered to be the biggest judicial corruption case in the history of Slovakia. From the mainstream media, readers firstly learned not only the names of the arrested judges and lawyers, but also what they were accused of, their profiles and their communication in the Threema app. On the contrary, the “alternative” initially took only a few facts from news agencies or other media, which they still tried to question. These considerations were even further sustained by the words from others, for example from Štefan Harabín, former minister for the HZDS party and favourite of the disinformation scene.

One of the main defendants in the case, Monika Jankovská, former State Secretary of the Ministry of Justice for Smer, only started to get more attention after her hunger strike. In an article by Aneta Leitmanová, Hlavný denník did not hesitate to describe her as both a brave woman and a victim of prosecutorial arbitrariness and malevolence. Apparently, only the editors know who wrote the article, as no journalist is publicly known by that name. However, the use of pseudonyms is common in the “alternative media”, while according to the Code of Ethics, a journalist does not hide his or her name.

In the Jankovská’s case, we also encountered questionable practices in some mainstream media. In August 2021, she was due to appear in court in an extortion case where she faced a prison sentence of between four and 10 years, but on arrival she was shaken, crying and unable to stand properly. Mainstream media offered live coverage of her arrival, and the videos are still available on the web today.

The Constitution guarantees every citizen the right to protection of their honour, dignity and privacy. However, in case of public figures, the limits of permissible criticism, use of portrayals and protection of privacy are less stringent than for ordinary people. It is undoubtedly in the public interest that the public should see that even a government official, in so far as he or she commits crimes, is not untouchable. However, the media should also respect human dignity.

The “alternative” have also declared a martyr the former head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office, Dušan Kováčik, who was finally sentenced to serve eight years in prison by the Supreme Court in May 2022 for accepting a bribe of 50.000 euros from the mafia and for disclosing information from files. The Extra plus monthly, which is owned by Lenka Mayerová, once close to the Mečiar’s HZDS party, also discussed the views of Smer’s deputy chairman Ľuboš Blaha. The magazine also featured his reflections on the “Matovič monster trial”, aimed at “purging opponents”, for which “not even the Stalinist prosecutor Urválek would be ashamed”.

Non-journalist genres

The Extra Plus article, whose editor-in-chief asks readers to pay for “what other media are silent about”, is a copy of Blaha’s Facebook status, which, by the way, is quite a common practice of “alternative media”. In the course of our analysis, we came across several “non-journalistic” genres of this type that are similar to mixing news with opinions without clearly distinguishing them. They tend not to verify the claims of politicians, which should be the primary job of journalists.

This is also how the “alternative”, lacking the critical point of view, adopted the claims of the Republika and Smer politicians about possible election rigging. The topic was also taken up by the mainstream, especially after the former minister Jaroslav Naď came out with the claim that “a citizen of the Slovak Republic was in Russia to take money in favour of Smer to rig the elections”. The mainstream media also drew attention to the fact that the issue of alleged risk of election rigging was not new and had been raised before the previous elections.

However, the topic that the “alternative media” most intensely covered was the close relationship between judge Pamela Záleská and journalist Monika Tódová in the period less than two months before the parliamentary elections.

Although their closeness was pointed out by re-elected Prime Minister Robert Fico as early as the beginning of 2021 and their relationship was also described as love by Blaha in his status at that time, the “alternative” only made it an issue before the 2023 elections, when controversial youtuber Martin Daňo filmed the journalist with the judge in a guesthouse. In the past, he was ordered to delete hateful videos about Tódová by the court, and he was also in custody due to like videos. The topic was on the headlines of the websites Hlavný denník, Hlavné správy, ereport, and Slobodný vysielač for several days. The relationship also became high profile for the mainstream tabloid Plus 1 deň.

However, the content published in the “alternative media” no longer even tried to come off as journalism in many instances. Apart from publishing one-sided statements without reactions from the main actors of the articles and conspiring about a group that manipulates court trials, they also constantly gave space to dehumanizing and insulting statements. Even the re-elected Prime Minister who used the aggressive rhetoric as a tool to win the next elections directed such statements at the two women.

Uncovered conspiracies

Notwithstanding, as the number one conspiracy case of the previous years in the “alternative” can be clearly identified the suicide of Milan Lučanský, the former president of the police force, which is discussed to this today. The narrative of his beating by the guards was spread in the public space by the Pravda traditional daily, which later tried to remedy the situation. Questioning the official investigation also filled the headlines of the Plus 1 Deň daily.

The “alternative” repeatedly conspired about a “political murder” without proper evidence. In December 2022, the Zem&Vek disinformation magazine published a text by Ivan Štubňa, “The death of Milan Lučanský was a planned political murder”, where the author also came to this “definitive” conclusion by using 61 question marks. (The text was also picked up as a blog by Hlavne správy).

The Infosecurity.sk project concluded that the topic of Lučanský’s suicide has become an important tool for creating the feeling that the government is abusing institutions in its fight against opponents, also with the help of disinformation scene. The then coalition was often accused of fabricated political trials. Lučanský, presented as a hero and a martyr, supposedly had to be silenced because he stood in the way of the government’s power interests and knew too much.

“The case of the death of Milan Lučanský, the former police president, will have a far-reaching impact on the development of Slovak politics,” predicted Robert Fico who eventually managed to reverse the downward trajectory of his popularity and became PM for the fourth time following early elections in September 2023.

Sympathy or money?

According to the aforementioned Focus survey for Transparency, the “alternative”, together with part of the political representation, was “successful” in this case, and thus at least 45% of the population does not believe the conclusions of the official investigation. As the recent public hearing of the now-named head of the police inspection Branislav Zurian showed, spreading this unfounded theory in direct contradiction to the results of the official investigation doesn’t present an obstacle to holding a high position in the police.

However, the significant overlap between the narratives of some of the current governing coalition and the “alternative media”, as well as the popularity of these politicians in their headlines, may not result only from small editorial teams simplifying their job or the personality makeup or preferences of the editors. Some of the published financial flows also point to more prosaic connections.

For example, the Smer party whose politicians encourage their supporters to read “alternative media” paid a total of 14.000 euros in August for unspecified media services to the publisher Extra plus – Mayer media, owned by the editor-in-chief Lenka Mayerová, a former assistant to MPs in the Mečiar’s HZDS party. The front page of the August edition was dedicated to Smer candidate and former police president Tibor Gašpar who is accused of corruption.

This is not an isolated case; other similar payments can be traced in the annual reports. Naturally, political advertising also occurs in the mainstream media, but the apparent affection of alternative media for some politicians also calls for caution when monitoring financial flows between politics and “alternative media”.

What to expect?

Immediately after winning the September elections, the new governing coalition has continued its confrontational attitude towards the mainstream media which is now even more prominent due to its friendliness with disinformation scene. The latter enjoys both privileged information and government support. Although so far, the elevation of the “alternative” to the new mainstream is rather wishful thinking of these parties, as our current analysis and survey show, their destructive impact on the quality of the rule of law and democracy cannot be underestimated.

The government’s protection of the “alternative” draws even more attention to these media which may, paradoxically, lead to at least some effort to raise journalistic standards. If only this was at least an unintended consequence of the new parliamentary majority. On the other hand, the convergence of the ruling coalition and the “alternative media” offers little hope for effective state policies against disinformation and hybrid threats. On the contrary, the risk is that the state will also lose expert officials who have been increasingly involved in strategic communication at various levels in recent years.

Slovakia is, fortunately, a member country of the European Union, which pays a lot of attention to disinformation in the media and on social networks. The Slovak Government thus won’t be able to ignore this issue completely. The counterbalance to the manipulations will be further represented by civil society and mainstream media. Like all of us, they are not without flaws, as our analysis has shown. They should be particularly wary of bias or other stumbles which the “alternative media” will exploit with great pleasure.

However, the tools to defend the rule of law and democracy are in the hands of all of us, and not only when we vote. We also shape society by the very media we watch, our expectations of their quality and adherence to journalistic standards, and our active support for those who act as the “watchdogs of democracy”.

Michal Piško, Martina Hilbertová, Ľuboš Kostelanský

Ján Ivančík and Kristína Kroková also contributed to the analysis

We wholeheartedly thank our excellent volunteer Sonička Kyselová for the translation of this analysis into English.

If the topics, such as the rule of law, the fight against corruption and disinformation matter to you, you can also support our work. Thank you!

The survey was supported by the European Media and Information Fund (EMIF). All content supported by the EMIF is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of EMIF and its partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.