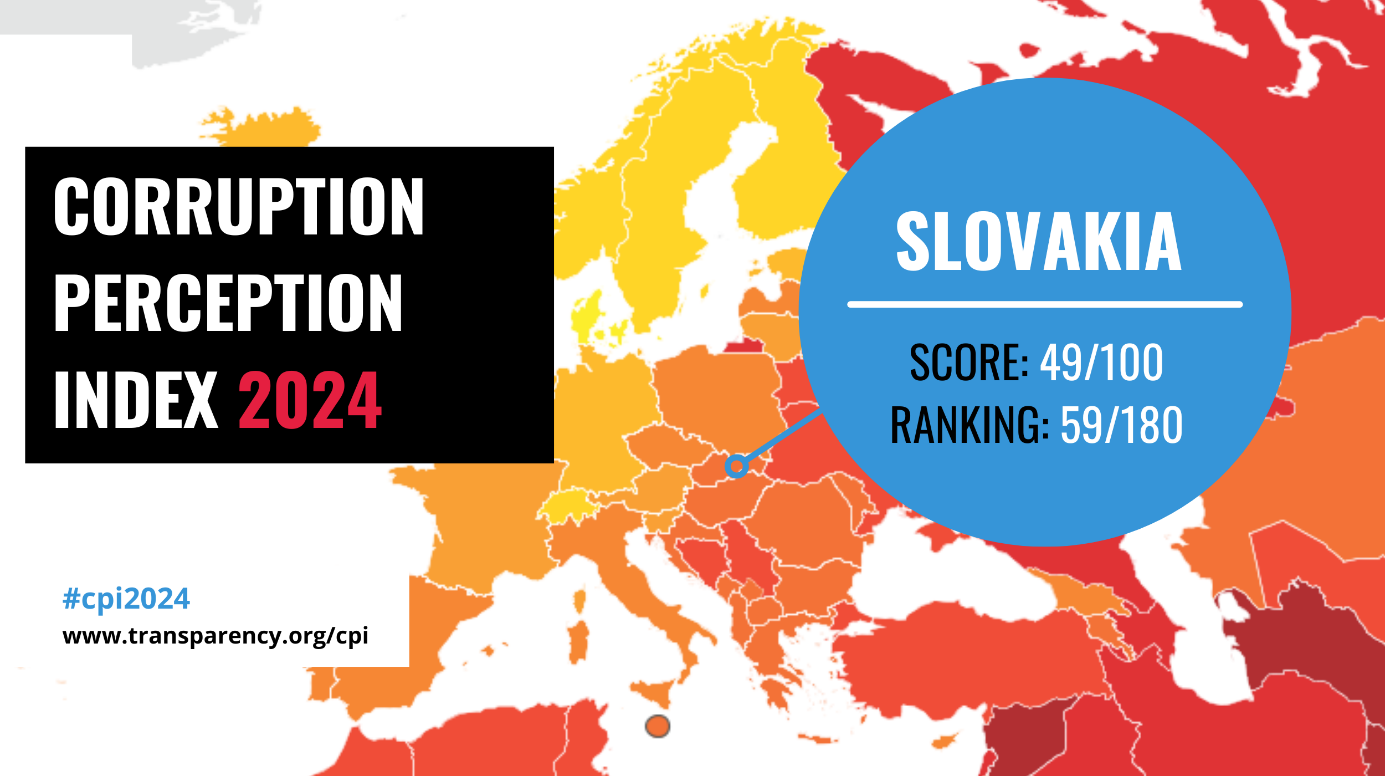

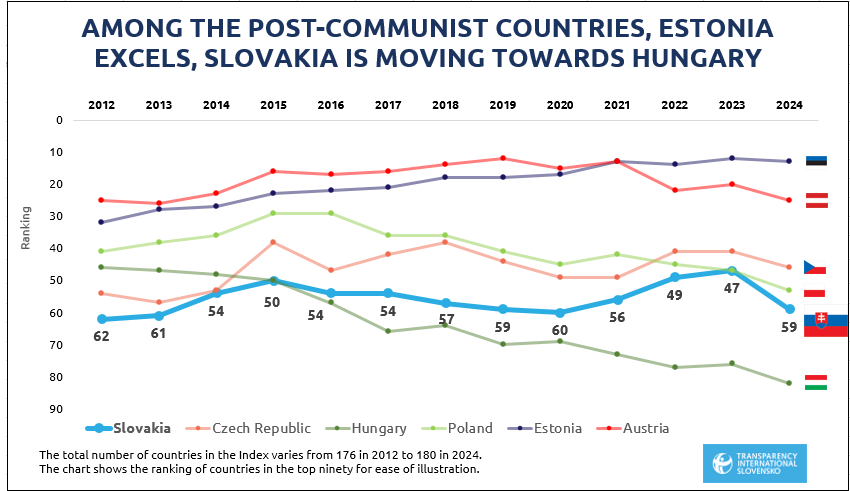

Slovakia dropped twelve places to 59th among 180 countries in the most cited corruption perception index (CPI), compiled annually by Transparency International’s headquarters in Berlin. This is a historic year-on-year drop from a best-ever ranking of 47th. It is also exceptional within the European Union, where only Cyprus and Malta have fallen more than us in the last decade between 2015 and 2016.

Also extraordinary is the drop in the score by 5 points from 54 to the current 49 points out of a 100 possible (the higher the score, the less corruption). In the current edition, like us, only six other countries have dropped year-on-year and only one has dropped more (Eritrea by -8 points). In terms of both score and ranking, we have thus fallen to the level of the results from the end of the third Fico government after the murders of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová.

The Global Corruption Perceptions Ranking is compiled on the basis of indices by independent institutions mapping one to two years back. Slovakia was covered by 10 of them, 9 of which covered the period of the fourth government of Robert Fico. Unlike last year’s ranking, which still reflected the period of the previous governments of Eduard Heger and partly also of Ľudovít Ódor, it is already a calling card of the current government.

Weakening the state in the fight against corruption

The sharp decline of Slovakia during the first year of Robert Fico’s government is given special attention by Transparency in the accompanying analysis on developments in Western European and EU countries. “Several reforms have weakened anti-corruption mechanisms and bypassed public involvement. The government abolished the Office of the Special Prosecutor and the National Criminal Agency, which were responsible for fighting corruption and serious crime. Combined with the shortening of statutes of limitations, the relaxation of penalties for corruption and the dropping of threatened sentences, these changes have led to a reduced ability to prosecute perpetrators as well as impunity in some high-profile cases,” summarises Transparency’s headquarters. It also recalls political appointments, the circumvention of standard legislative procedures and the government’s undermining of independent institutions and media, along with attacks on NGOs through Russian-style ‘foreign agent’ narratives.

Slovakia’s fall in the ranking is largely in line with the perception of last year’s development by a hundred domestic experts and personalities. Experts in the field of the rule of law, political scientists, sociologists, analysts, economists, businessmen, journalists, former politicians, well-known personalities and representatives of the public sector were approached by Transparency Slovakia at the turn of the year as part of the “Expert Consultation on Corruption – Slovakia 2024“. As many as 86 percent of respondents expected Slovakia to deteriorate in the CPI 2024, while 28 percent predicted a noticeable drop. Meanwhile, nine out of ten respondents do not believe the current government is interested in tackling corruption.

Politically motivated changes to criminal codes without proper public debate have led to de facto “amnesties” in a number of corruption cases. Influential people with links to politics, such as former Finance Minister Ján Počiatek and probably his successor Peter Kažimír, acting parliamentary speaker Peter Žiga, and businessmen Miroslav Výboh and Peter Košč, will avoid a fair trial and possible punishment because of the shortened statute of limitations.

The government also helped former special prosecutor Dušan Kováčik, who was convicted for a bribe in favour of the mafia. He was released on the basis of an appeal and a decision to suspend the sentence of Justice Minister Boris Susek. The Supreme Court will decide the appeal, while Kováčik was also convicted in the first instance for another bribe. The man who was originally supposed to represent the state in the fight against corruption from the front row has thus repeatedly become its symbol.

Legislative and systemic changes in the form of the abolition and reorganisation of specialised corruption units have also had an impact on performance. The new successes of law enforcement agencies, after years of uncovering serious cases, have hardly been heard of since last year. According to its own statistics, in 2024 the police both detected and cleared just under 50 corruption offences. The number of offenders under investigation has fallen to 90 in the past two years, the lowest figures in a decade.

Rule of law and public scrutiny under pressure

The weakening of the rule of law is also an important context. This has manifested itself not only in the escalating attacks by some politicians against some investigators, prosecutors, judges, independent institutions, the media and civil society, but also in the poor quality of the legislative process. Fundamental changes have been pushed through parliamentary motions or fast-track procedures without public debate. Standards on the right to information, public procurement, public television and radio, and support for cultural and civic initiatives have also undergone negative changes in terms of public scrutiny. An amendment targeting NGOs has also been pending in Parliament for three quarters of a year.

The coalition continues its political purges, ministers of Robert Fico’s fourth government replaced up to 55 percent of senior positions in ministerial organisations in the first year alone, according to an analysis by Transparency International Slovakia. The campaign before the presidential elections, which was affected by unfair practices and the circumvention of electoral rules, also left a negative aftertaste.

The European Commission’s Rule of Law Report 2024 also critically assessed the developments, according to which Slovakia has made no progress on almost none of the previous recommendations. In the autumn of 2024, the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO), a body of the Council of Europe, also accused Slovakia of failing to implement recommendations on fighting corruption and strengthening integrity in government and the police.

While not all of the government’s controversial plans government has implemented, the vocal rejection of the undermining of the rule of law by a significant part of the public remains a positive development.

Fall also among EU countries

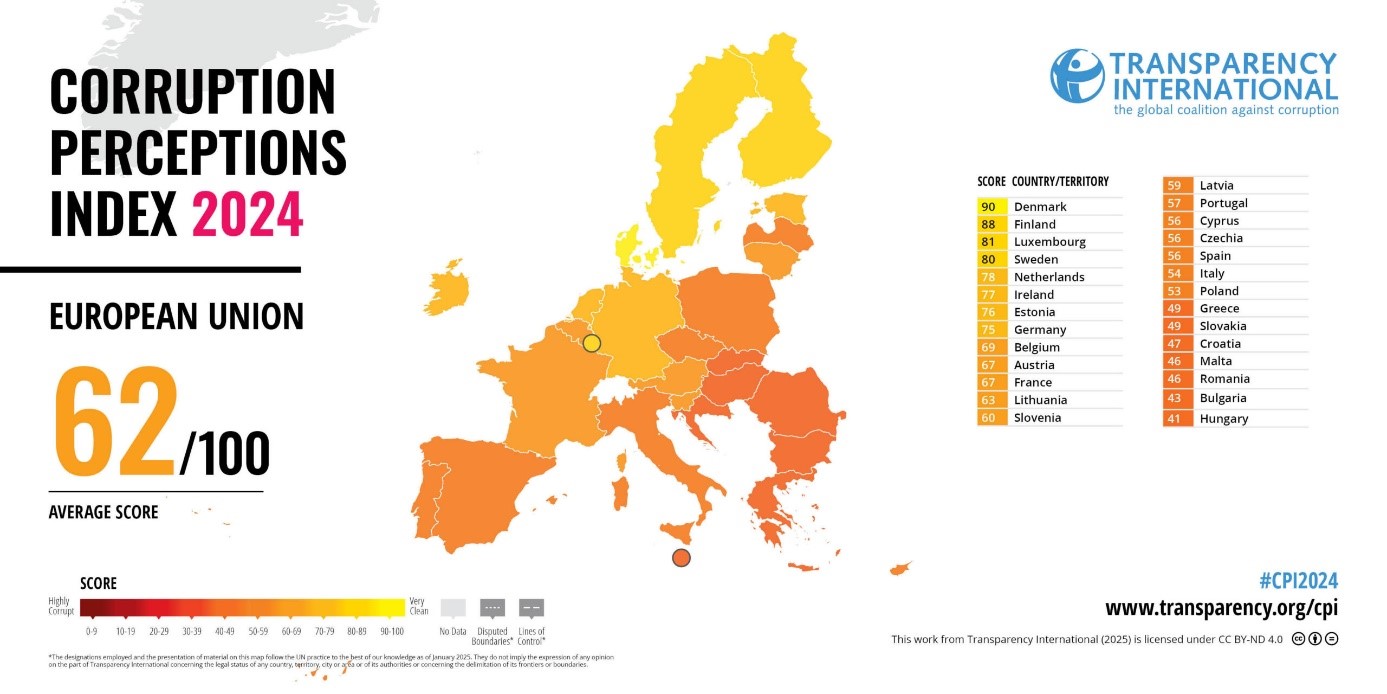

In the CPI ranking for 2024, Slovakia’s lag behind the average of the European Union countries has also increased. While last year we were 10 points behind the EU average, currently it is already 13 (49 vs. 62 points). Only five EU countries were worse off than us – Croatia (63rd), Malta (65th), Romania (65th), Bulgaria (76th) and lastly Hungary (82nd). We were matched by Greece (59th) and overtaken by Cyprus (46th).

The countries with the least perceived corruption in the world remain Denmark with a score of 90, followed by Finland (88) and Singapore (84) in third place, behind New Zealand (83). Of the post-communist countries, Estonia is the highest scoring, currently ranked 13th in the world with 76 points. Among the Visegrad 4 countries, the Czech Republic (46th with a score of 56) and Poland (53rd with a score of 53) are ahead of us and slightly worse off. Further down is Hungary, which remains hopelessly last in the EU (82nd position with a score of 41).

What will 2025 be like?

The change of course on the rule of law and the fight against corruption, as well as on foreign policy, is reflected in the approach of the ruling coalition at the beginning of 2025, when massive anti-government protests are taking place across Slovakia. These are downplayed by the ruling coalition, or even sought to be linked to alleged coup attempts.

The political instability and the possibility of early elections also make the development estimates more difficult to assess, but this may also act as a brake on fundamental anti-democratic changes. However, the consequences of the deteriorating situation in the area of corruption and the rule of law will be felt domestically and by foreign partners and investors in the period ahead. A further drop in the rankings may also mean Slovakia breaking through the current low (62nd place), which it reached in 2012 using today’s methodology.

Corruption also exacerbates the effects of climate change

The situation has not changed at the tail end of the ranking. Among conflict-torn countries with failing states such as South Sudan (180th position and 8 points), Somalia (179th and 9 points) and Syria (177th and 12 points), Venezuela (178th and 10 points) has settled in. Of the European states, declining Russia (154th with a score of 22) was again the worst ranked; corruption remains a major problem even in its embattled Ukraine (105th and 35 points).

Over the past decade, only 24 out of 180 countries have been able to improve significantly their resilience to corruption, while in 32 countries the situation has noticeably worsened. As many as two-thirds of the countries have not even reached half of the possible points in the current ranking, with Slovakia currently among them with 49 points.

In this year’s CPI report, Transparency Central also highlights the risks of corruption in the context of the consequences of the climate crisis. “While billions of people around the world face the consequences of climate change every day, resources for adaptation and mitigation remain woefully inadequate. Corruption exacerbates these challenges and poses additional threats to vulnerable communities,” the movement warns.

What does the CPI measure?

The Corruption Perceptions Index has been compiled by the organisation since 1995, and the current results have been comparable year-on-year since 2012. The rankings are calculated from the performance of countries in 13 different indices by independent institutions including the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, as well as consultancies and think tanks. Transparency International is not involved in their creation.

Slovakia’s current score is based on its ranking in 10 indices. Slovakia’s score has deteriorated in half of them, most notably in the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook of the Swiss Institute for Management Development and in the SGI Sustainable Governance Index of the German Bertelsmann Foundation (which covers the two-year period until January 2024).

The resulting corruption perception ranking, based on more detailed indices, thus reflects mainly the perception of corruption among managers, investors or Slovak and foreign experts. Compared to Eurobarometer surveys examining public opinion, the aggregate CPI index is more reflective of developments in the area of grand corruption (abuse of public functions and resources, clean tenders, anti-corruption actions of the government, level of the rule of law, etc.). Details of the methodology and full results are available on the Transparency International headquarters website. The Slovak context can also be seen in a short video.