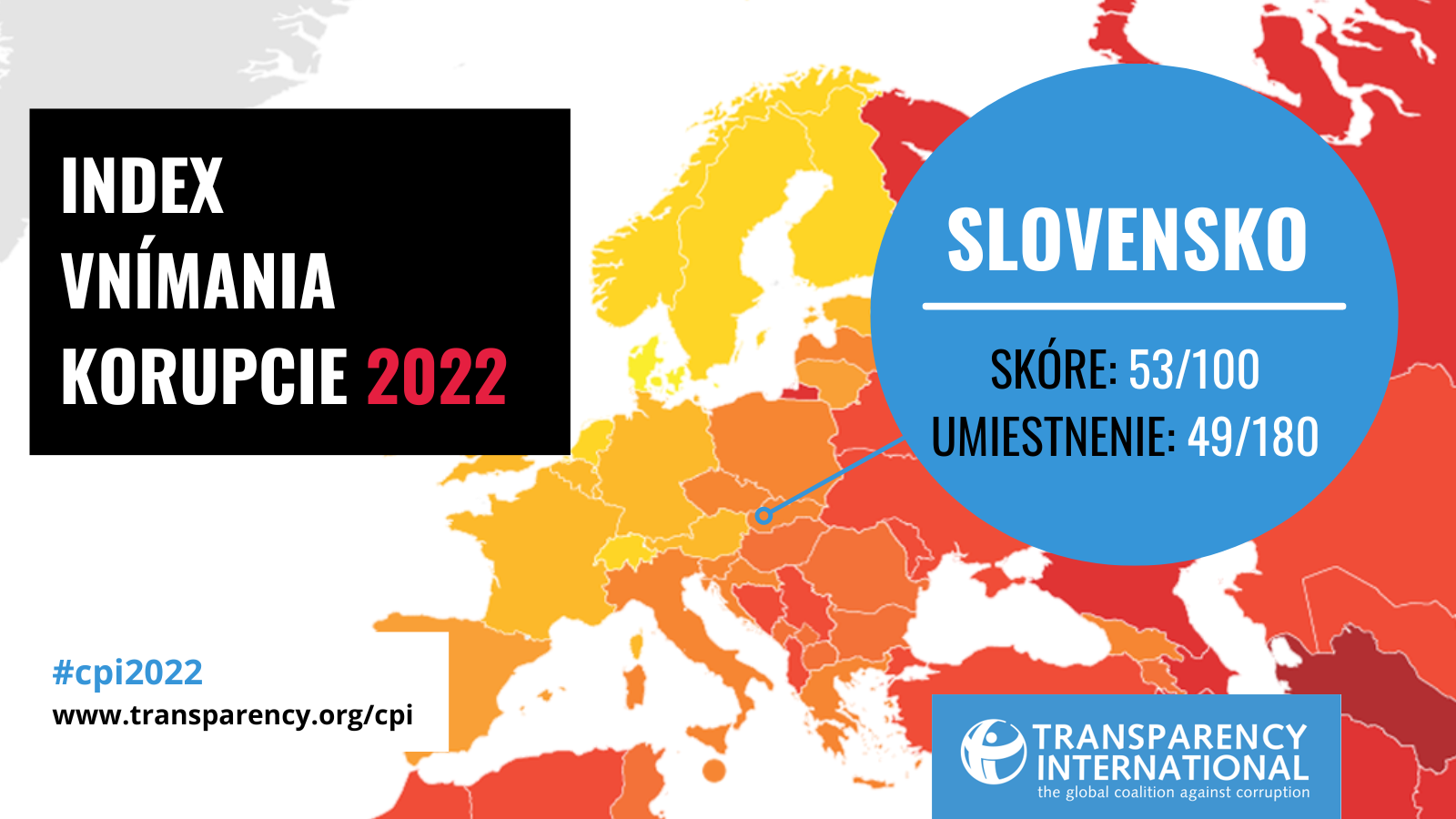

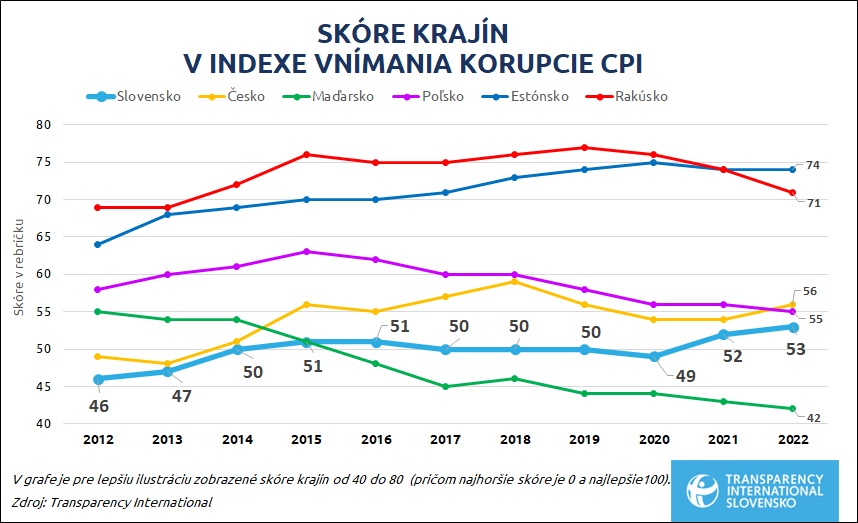

Slovakia has improved in the most cited Corruption Perception Index (CPI), compiled annually by Transparency International, and ranked 49th out of 180 countries assessed. The resulting position in 2022 is thus seven places better than the previous year (56). Nevertheless, the shift is only slight, as Slovakia’s final score improved by one point from 52 to 53 out of 100 points (the higher the score, the less corruption). The noticeable shift in ranking is, therefore, also a consequence of the stagnation or downswing of other countries of a similar level.

But still, the resulting placing within the top fifty and the final score are the best since the methodology was modified in 2012. If we compare the 2020 ranking (reflecting, with hindsight, the period of the government of Peter Pellegrini in particular) with the current ranking, Slovakia has managed to move up 11 places in two years.

The government’s ambition stated in its programme statement to improve Slovakia’s ranking by 20 positions is thus half-fulfilled. The current electoral period will still be reflected in next year’s ranking, but given the recent vote of no confidence in the government and the early elections, any further substantial progress is unlikely.

What is behind the improvement?

The Corruption Perception Index is calculated from the results of indices of various institutions that reflect corruption from the perspective of entrepreneurs, investors and experts within the period of one or two previous years. The current result is thus mainly a reflection of their perception of the anti-corruption setting of public institutions under the government of Eduard Heger (OĽaNO, Ordinary People and Independent Personalities).

Same as last year, Slovakia’s current improvement can be attributed primarily to the continued efforts of the police and the prosecution service in detecting and prosecuting corruption and abuse of power. The results, however, were somewhat unconvincing, especially because of the actions of Attorney General Maroš Žilinka, who repeatedly cancelled prosecutions and withdrew charges through the controversial use of Section 363 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

The police and the Special Prosecutor’s Office had to deal with his reservations about their work in the cases of influential businessmen Zoroslav Kollár, Peter Brhel and Jaroslav Haščák, top politicians such as former Prime Minister Robert Fico, former ministers Robert Kaliňák and Peter Kažimír, as well as the former head of the Slovak Information Service and a nominee of the current government Peter Pčolinský.

Interim statistics of the General Prosecutor’s Office show a slight decline in the prosecution of corruption offences. While over 250 people (an all-time high) were prosecuted for this category of crime in 2021, last year, the prosecution service recorded 168 cases. Compared to the previous year, the number of defendants has also fallen by 40%, and an analysis of sentences for the first three quarters of the year shows that fewer cases have reached a resolution in court. On the positive side, however, there has been a significant increase in convictions for corruption involving a bribe of more than €5,000, which in the past constituted only a marginal part of the decisions.

The final conviction of the former special prosecutor Dušan Kováčik, who had formerly been responsible for prosecuting corruption, to eight years in prison for having accepted a bribe from a member of a criminal group, was the most prominent of the big cases concluded in 2022. Several former officials and police officers have also been convicted, including Pavol Vorobjov, the former head of the National Criminal Agency’s financial intelligence unit, who cooperated with organised crime and illegally vetted journalists and prosecutors in exchange for bribes.

Final verdicts have already been reached for some of the accused businessmen, for example, in the Mýtnik (Toll collector) case concerning overpriced tenders in the Financial Administration. The court also approved a plea agreement in the case of bankruptcy lawyer and entrepreneur Zoroslav Kollár.

Conflicts weakening the capacity for action

The government’s anti-corruption plans, which the ruling coalition set out in its programme statement, have brought only limited progress. Major corruption cases were avoided by its leaders, but the quarrelsome way of governing provoked negative reactions in society and paralysed the government’s own ability to act. Criticism has also been levelled at the weak political culture and the practice of circumventing the legislative process.

The coalition’s lack of will to reform the prosecution service is disappointing, and we have not made any significant progress in ensuring the independence of police inspections. The reform of the judicial map ended with a delay; a debate on changing the penal codes was triggered by unfounded considerations of some politicians about reducing penalties for corruption.

Some prosecutors, experts and politicians, including President Zuzana Čaputová, have repeatedly pointed out the considerable overuse of Section 363 of the Criminal Procedure Code by the Prosecutor General, leading to a disproportionate interference in the independence of the judiciary. However, despite its commitment to the programme declaration, the ruling coalition has not been able to change this regulation due to their internal disputes.

Positives include the legislative strengthening of the public’s right to information, the initial activities of the new Whistleblower Protection Office or the Supreme Administrative Court, and a greater number of transparent selection procedures for the heads of public institutions. However, shortcomings persisted here as well. Instead of de-politicising more systematically the election process for the director of the Radio and Television of Slovakia (RTVS), the coalition only established a one-off expert committee; the new ombudsman was elected only after seven months of paralysis; and both the Antimonopoly Office and the Office for Personal Data Protection have been occupied by nominees of past governments for over a year.

The government’s promises related to legislation on proofs of the origin of assets, lobbying, material responsibility of public officials, control of their assets and more detailed asset declarations have not yet been enforced.

“The judiciary and law enforcement have exercised their newly found independence in Slovakia, pursuing several high-profile corruption cases. However, political infighting has weakened anti-corruption efforts. In December 2022, a no-confidence vote brought down the government. With politicians embracing divisive rhetoric ahead of the early parliamentary elections later this year, there is the danger that recent progress will be reversed and democracy will deteriorate,” summarises Transparency International as regards Slovakia’s outlook for the near term in the report on the ranking of developments in Western Europe and the EU.

We are approaching the EU average rather slowly

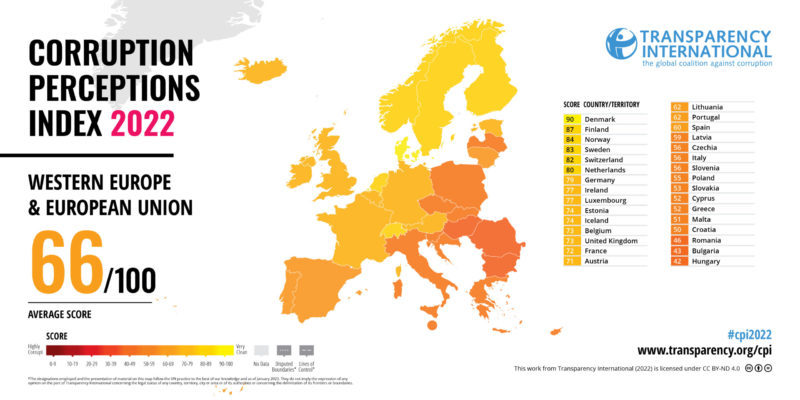

Despite improving its ranking two years in a row, Slovakia is still noticeably lagging behind the average of the European Union countries (53 points vs. the EU27 average score of 64 and vs. the Western Europe + EU average score of 66). Unlike in the past, this time, we left behind seven countries of the EU27, overtaking Cyprus (51st place) and Malta (54th). Greece (shared 51st place), Croatia (57th), Romania (63rd), Bulgaria (72nd) and Hungary (77th) finished behind us as well.

There were two EU countries among the top three least corrupt states: Denmark (first overall with a score of 90) and Finland, which, together with New Zealand, scored 87 points. Among the post-communist countries, Estonia is still the highest (14th place and a score of 74). Among the Visegrad Four countries, both the improving Czechia (41st position and a score of 56) and the declining Poland (45th position and a score of 55) are ahead of us.

The same trio of conflict-torn states as last year finished at the tail of the ranking: South Sudan and Syria (identically scoring 13 points), and Somalia at the last 180th position with 12 points. Russia is again the worst-ranked of the European countries (137th with a score of 28), while Ukraine, suffering from Russian military aggression, is currently 116th with 33 points.

From a longer-term five-year perspective, a more noticeable drop in the ranking can also be observed for a number of Western countries such as the UK and Canada (-7 points), Austria (-5 points) or Luxembourg (-4 points). While these countries are still very high in the ranking, and their scores are indicative of well-functioning institutions, their results suggest that there are problems even at the top of the ranking. These challenges have been further exposed by the invasion of Ukraine, as the West struggles to detect and combat dirty money. The territories and legislation of these states are also being used by oligarchs and criminals from countries like Russia to launder money.

What the CPI reflects

The Corruption Perceptions Index has been compiled by Transparency International since 1995, and the current results are comparable year-on-year since 2012. The ranking is calculated based on the results of the countries in 13 different indices developed by independent institutions, including the World Bank and the World Economic Forum, as well as consultancies and think tanks. Transparency International is not involved in their development.

Slovakia’s current score is based on a ranking in 10 indices (which is also the maximum number for a single country), with improvements in half of them. Slovakia has made the biggest progress in Sustainable Governance Indicators of the German-based Bertelsmann Stiftung Foundation and in the competitiveness comparison of the Swiss-based International Institute for Management Development (IMD).

The assessment thus reflects mainly the perception of corruption among managers, investors or Slovak and foreign experts. Compared to Eurobarometer surveys of public opinion, the aggregate CPI index is more reflective of developments in the area of grand corruption (abuse of public functions and resources, clean tenders, government anti-corruption measures, etc.). Details on the methodology of the ranking and the full results are available at the Transparency International headquarters website.

If you have further questions, you can contact the Slovak office of Transparency International.

Michal Piško, Transparency International Slovakia director

- Press release

- Analysis: Corruption prosecutions are on the rise, the number of punishments is increasing, and it is not just about small fry anymore

Kontakt: tis@transparency.sk, 0905 613 779